California Country Club Estates

California Country Club Estates covers the grounds of the former California Country Club which Culver City founder Harry Culver established next to his Castle Heights home. In 1950, the club’s then-owners – actor/director Frank Borzage, actor/singer Fred MacMurray, Hollywood manager Bö Roos, and actor/filmmaker John Wayne – sold to Sanford Dennis “Sandy” Adler (1909-1991), who developed the neighborhood in its place, starting in 1951. Sanford Adler had been many things: homebuilder, developer, hotelier, casino operator and Mob front man. Covered in hundreds of newspaper articles during his lifetime, Sanford Dennis Adler’s death was barely noted in the Los Angeles press, when he passed away on June 13, 1991. The balance of this page, then, focuses on Sanford Adler.

Builder from Detroit

Sanford Adler was born in Providence, Rhode Island, the son of Eastern European Jewish immigrants. In Detroit, Michigan, he worked for builder Edward Rose (patriarch of Edward Rose & Sons) and started his own homebuilding company, Sanford D. Adler, Inc. (Detroit Jewish News, July 5, 1991 (obituary).) Before leaving Detroit, Adler built homes in the Sherwood Forest Neighborhood. Sherwood Forrest had (and still has) a mandatory homeowners’ association – perhaps the inspiration for the association Adler would set up when he built California Country Club Estates. His Sherwood Forest houses include one for Max Martin Fisher (1908-2005), 19240 Parkside Road (Nov. 15, 1940) and another at 2845 Cambridge Road (Jan. 3, 1941).

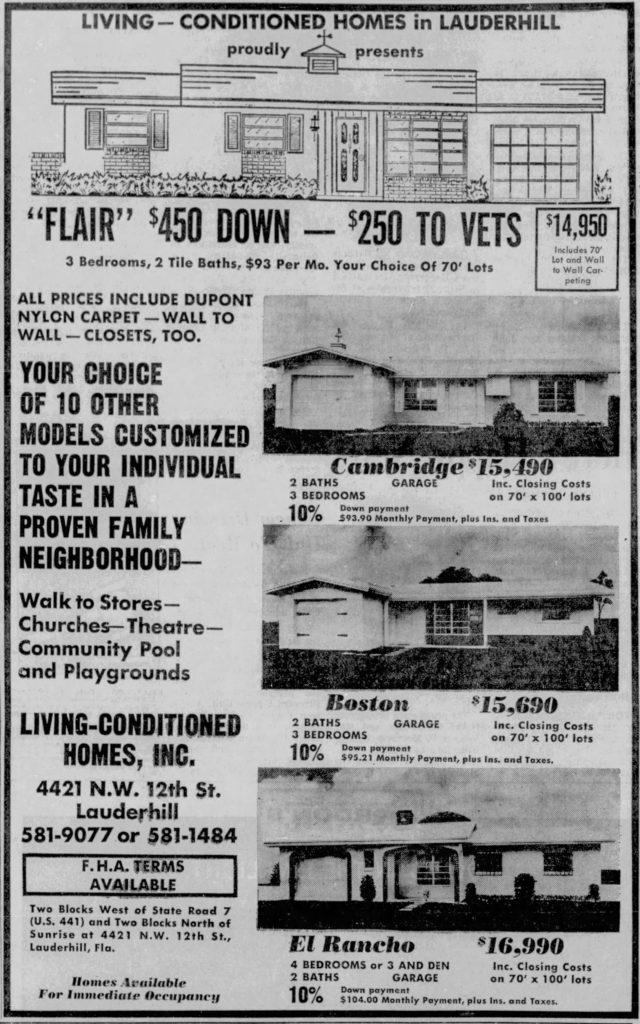

After becoming wealthy “selling some 5,000 housing lots in Detroit” (Mob City: Reno (p. 149), Sanford Adler left “Detroit to develop hotels and subdivisions in Florida and California.” (Detroit Jewish News, July 5, 1991.) In the early-1950s, West Los Angeles’ California Country Club Estates neighborhood was his first, while his San Fernando Valley developments are better remembered. By the mid-1960s, he was building smaller homes in South Florida through his Living Conditioned Homes, Inc. company. There is even an eponymous 9-lot subdivision (Sanford D. Adler Sub 76-16 B) in Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

Sanford’s son, Brian Dennis Adler, was president of another Adler Florida building company: Living Conditioned Homes Corp. But Brian Adler appears to have been more active in Los Angeles, where he was “co-owner of Harleigh Sandler Realtors and co-founder of Rodeo Realty, which he sold to Merrill Lynch Realty in 1982.” (L. A. Times, Feb. 12, 1989.) Brian’s Beverly Park development, “a 325-acre, guard-gated estate enclave adjacent to Beverly Hills” “is considered to be the premier guard-gated enclave in the United States.” (MansionCollection.com, Brian D. Adler, Co-Founder/Owner/ President & Managing Broker (California).)

Hotelier & Casino Operator (1945-1956)

Adler’s move west traces back to 1945. On September 2, the Los Angeles Times reported, under the headline “Rosslyn Hotel Purchased by Detroit Man,” “The 1100-room Rosslyn Hotel and Annex at Fifth and Main Sts. . . . has been acquired . . . to be added to the hotel holdings of Sanford D. Adler, Detroit . . ..” The reported price was $1,500,000.

A couple of weeks later, on September 17, 1945, the Times reported, “Purchase of Hotel Del Mar by Sanford Adler for a reported consideration of $750,000 ….” It concluded, “Adler also owns the Rosslyn Hotels in Los Angeles and others in the East.” This author has not learned anything of other Adler hotels “in the East.”

In March 30, 1946, the Times reported that Adler had paid $450,000 for the “Normandie Hotel property and equipment at the corner of Sixth St. and Normandie Ave.”

That was about the same time he got the El Rancho Vegas. “Thomas ‘Tommy’ Hull, an experienced hotel man (at the time he operated the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel and the Miramar Hotel in Santa Monica) . . . built the El Rancho on a nearly bare stretch of desert along Highway 91– the Los Angeles Highway – just outside the Las Vegas city limits.” (J. H. Graham, El Rancho Las Vegas.) “The Hotel El Rancho Vegas opened on April 3, 1941. It was the first resort casino-hotel on the strip.” It was an addition to Hull’s “chain of ‘El Rancho’ hotels in Gallup, New Mexico, and Fresno and Sacramento, California. The 63-cabin resort was designed as a way-station, a break for families to enjoy on their trip through Nevada, not as a casino property.” (Nevada Casino History website.)

In March 1946, “it was reported that [Joe] Drown had leased the El Rancho to San Diego hotel man Sanford ‘Sandy’ Adler, who headed up a ‘local syndicate of several corporate investors.'” (J. H. Graham, El Rancho Las Vegas.) “Charlie [Resnick], who was allegedly connected with Detroit’s ‘Purple Gang‘” was one of those investors according to OnlineNevada.org.

In July 1947, Adler bought Las Vegas’ Flamingo Hotel. The L. A. Times reported, “One of Benjamin (Bugsie) Siegel‘s rival hotel owners bought the slain gangster’s ornate Flamingo casino for $3,000,000. He is Sanford D. Adler, who by the deal became president both of the Flamingo and El Rancho Las Vegas.” Larry D. Gragg goes into more detail:

The two men [Moe Sedway and Morris Rosen] found an eager buyer in Sanford Adler, who owned the El Rancho Vegas. Louis Weiner Jr. helped Adler form a corporation called Flamingo Hotel, Inc., with Adler controlling 49 percent of the stock. Other investors included Moe Sedway, Gus Greenbaum, Morris Rosen, and Dave Berman. The Adler group, which included Charlie Resnick of the Detroit Purple Gang, paid $3.9 million to the Nevada Projects Company and took possession on July 16, promising “no major managerial or top personnel changes.”

Larry D. Gragg, Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel: The Gangster, the Flamingo, and the Making of Modern Las Vegas (Praeger, 2015), p. 139.

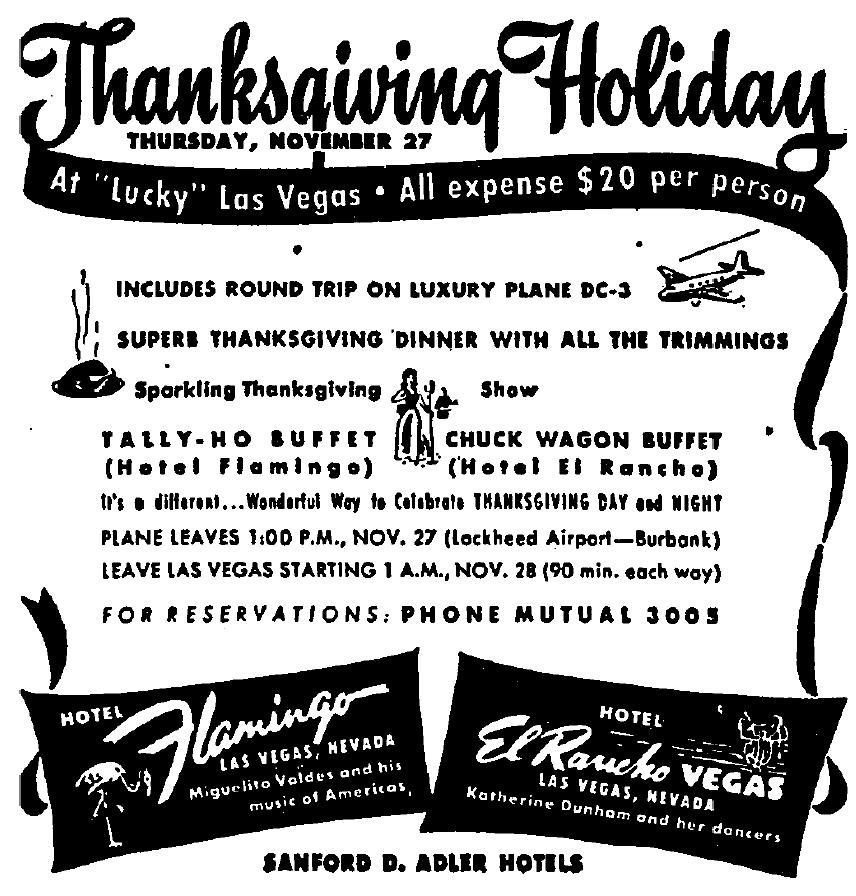

The aforementioned Moe Sedway and Gus Greenbaum were mobsters whose names may have been merged to inspire the name for the character “Moe Greene” in The Godfather. In November 1947, Adler controlled both the El Rancho Vegas and Flamingo, and he advertised for Angelenos to fly to Las Vegas for Thanksgiving.

Adler also marketed the Del Mar Turf and Surf Hotel with his Las Vegas properties: “Vacation Time At Your Favorite Resort Hotel” read the copy of an October 15, 1947, L. A. Times advertisement, featuring all three of the hotels.

Sanford Adler did not run the Flamingo for long. On April 16, 1948, the Los Angeles Times reported he would be selling:

Sanford D. Adler, hotel operator, yesterday disclosed that he has granted an option for the purchase of his controlling interest in the Flamingo Hotel at Las Vegas, Nev. The option, given to Gus Greenbaum and other stockholders of the hotel, has an expiration date of next July 15.

Adler acquired a majority of the stock in the Flamingo from the estate of Benjamin (Bugsy) Siegel last July 16 after Siegel was murdered in Beverly Hills. Since obtaining control of the hotel, Adler has been active in its management.

Although he declined to reveal the amount of the offer made to him by Greenbaum and the other stockholders, Adler yesterday said, “It was so good, I couldn’t turn it down.”

Adler also operates El Rancho Vegas in Las Vegas and the Rosslyn and Normandie hotels here.

With apologies to The Godfather author Mario Puzo, did someone make Adler an offer he couldn’t refuse? Albert Woods (“Al W.”) Moe, in The Roots of Reno (2008) (p. 205), put Adler’s position at the Flamingo this way:

. . . when Bugsy Siegel was shot, Adler was asked to run the Flamingo. He was certain he was in charge, even though he only had to put down $195,000 to own half of the then $3.9 million property. He was not. He was the front man.

Beverly Hills Police Chief Clinton H. Anderson, testifying before the Senate Crime Investigating Committee (popularly known as the Kefauver Committee), gave his take on Adler’s leaving the Flamingo:

The officer mentioned as another individual interested in the Las Vegas set-up Morrie (Doc) Rosen, whom he described as a New Yorker who had dominated liquor distribution in Puerto Rico.

The very morning of the Siegel slaying, Chief Anderson said, “certain members of the group” interested in the Flamingo, including [Moe] Sedway, walked into the hotel and advised “certain people that they were taking over.”

Later, he said, after a dispute over control of the hotel led to litigation decided in favor of a faction represented by Sanford Adler, Adler came to blows with Rosen, representing the opposing faction, who finally exclaimed: “‘There’s blood on our hands now and you’re not going to get away with this.'”

The chief said Adler had reported this comment to him personally, and promised to assist him in further investigation of the Las Vegas dispute, but had left this section of the country and had never returned as far as he knew.

L. A. Times (Feb. 28, 1951). According to Al W. Moe’s Mob City (p. 149), Adler lived in Chief Anderson’s jurisdiction (608 Trenton Drive, Beverly Hills).

The Kafauver Committee highlighted Adler’s underworld connections and called him “a gambler with a long record of arrests”:

Until his death by violence, Siegel had a controlling interest in the Flamingo Hotel at Las Vegas, one of the country’s most elaborate gambling establishments. Associated with Siegel in the hotel and its gambling enterprises were Moe Sedway, Allan Smiley, a gambler with a long criminal record who came to Las Vegas with Siegel, Meyer Lansky, and Morris Rosen also old-time associates of the New York mob.

After Siegel’s death the operation of the Flamingo was taken over by Sanford Adler, a gambler with a long record of arrests, and a number of his associates. Adler entered into an agreement with Sedway, Rosen, and Gus Greenbaum who controlled the wire service in Phoenix. Under the agreement, Adler was to have control over the operation of the hotel, although Rosen, Sedway, and Greenbaum held the controlling number of shares in the hotel. After a violent disagreement with Greenbaum, Adler suddenly sold out his interest and retired to his gambling clubs in Reno and Tahoe, leaving Greenbaum, Rosen, and Sedway in undisputed possession of the lucrative Flamingo operation.

May 1, 1951, interim report, Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce, p. 91.

This author does not have the so-called “long record of arrests,” but a couple are found in newspapers. First, in August 1947, Adler “was booked on a charge of possession of gambling equipment . . . after a Sheriff’s raid on the Hotel Del Mar garage.” “Sheriff Bert Strand said Adler . . . was booked on a misdemeanor charge of violating a county ordinance prohibiting possession of gambling equipment and was released on $250 bail. Sheriff Strand termed the raid a ‘prevention move.’ No one was operating the games.” (L. A. Times, Aug. 9, 1947.) “The equipment seized was roulette wheel, three dice tables and two blackjack tables, which Henry Paronelli [who claimed to be their owner, and to whom Adler said he had leased the garage] valued at $55,500.” (San Bernardino Sun, Aug. 12, 1947.) A retrial was set for January 15, 1948, after Adler’s “first trial ended Nov. 20 when the jury reported an 11-to-1 deadlock.” (L. A. Times, Nov. 28, 1947.) Which way the 11-1 jurors had tilted and whether a retrial was held has not been uncovered.

A year after the gambling machine arrest, in August 1948, the Los Angeles Times reported Adler’s arrest at his home (by the police “antigangster squad”) on a two-year-old battery warrant: The battery complaint, according to police, grew out of an argument in February, 1946, between Adler and Morris Weiss, 65, whom the hotel man had hired to do some upholstery work. Weiss complained that Adler kicked him, police said, but Adler was quoted as saying he “only gave him a shove.” Adler had been arrested after he failed to appear for trial. He posted bail, and sprinted a block away before stopping for newsmen to take his picture, explaining, “I just didn’t want my picture taken in jail. I’ve got kids, you know.” It is not clear if criminal charges were pursued, but Morris Weiss lost his $20,035 civil damage suit. (L. A. Times, Nov. 24, 1948.)

Despite his “long record of arrests,” Adler was licensed to run El Rancho Vegas “after Wilbur Clark, Moe Dalitz’ front man, left in 1947″ (Al W. Moe, The Roots of Reno). With a casino license, Adler was able to stay in the Nevada casino business setting up shop in Reno and Lake Tahoe.

On June 4, 1948, along with Charles Resnick, Mr. Adler bought Lake Tahoe’s Cal-Neva lodge from Elmer ‘Bones’ Remmer San Francisco hotelman, for $700,000 or $800,000. (Reno Gazette Journal, June 4, 1948; Long Beach Independent, June 5, 1948.)

Next, on September 11, 1948, Adler and Resnick bought Reno, Nevada’s Fordonia Building (which had held the Zemansky Brothers’ Club Fortune) from Jack Sullivan and Jim McKay for “$350,000 cash.” (Sacramento Bee, Sept. 11, 1948.) The Online Nevada Encyclopedia reports the sale “to a group of Jewish investors including Sanford Adler, Louis Mayberg, Morris Brodsky, and Charles Resnick” and says they “spent a half million dollars remodeling the facility, which became the Club Cal Neva.” (Jews in Reno Gaming); Mob City, p. 113.)

Then, in October 1952, Adler and Resnick bought the Tahoe-Biltmore. “Charles Resnik [sic], an Adler partner, said the firm, operators of the Cal-Neva lodge at the lake and the Club Cal-Neva in Reno, had paid approximately $350,000 to Joseph Greenbach, a California hotel operator, for the lake resort.” The Adler group bought the Tahoe-Biltmore as an “annex to Cal-Neva.” (Reno Gazette-Journal, Oct. 16, 1952.)

“Bones” sold his Calneva casino to Sanford Adler and Charles Resnick for $800,000. Adler, seemingly awash in cash, paid over $500,000 for remodeling of the Club Cal-Neva in Reno, and then spent only slightly less at the Lake Tahoe site. After the government auctioned off the Tahoe Biltmore, he purchased it from the winning bidder for $350,000 and used it for overflow lodging from the Calneva. (The Roots of Reno, p. 183.) As for the casino’s name, “Adler, who had opened the Cal-Neva in Reno, changed the lodge’s spelling to match his club in Reno, and thus the Calneva Lodge became the Cal-Neva Lodge.”

Al W. Moe, The Roots of Reno, p. 205.

The new casino, called the Tahoe Biltmore, was fronted, but actually put together by Sam Termini. Also known as Sam Murray, the San Mateo County gaming club owner was being backed by his godfather, Charles Binaggio. . . ..

Before the casino was finished, Binaggio was the victim of a mob hit . . ..

The [Internal Revenue] Bureau decided that Termini owed $303,000 in back taxes. The commission also raised the names of Elmer “Bones” Remmer, and Eddie Sahati. Both were running [illegal] gaming in the San Francisco Bay Area in the 1940’s ….

However, Sanford Adler could not withstand government scrutiny for long. “Newspaper accounts placed him in a group of known mobsters like Joey Adonis, Meyer Lansky, and Frank Costello.” (Al W. Moe, Mob City: Reno (2013), p. 149.) He was looking to sell in December 19, 1954, with the San Bernardino County Sun reporting (from the AP wire) that the “Internal Revenue Bureau recently filed $78,000 in tax liens against three gambling establishments owned by Adler.” “In October of 1955, he and his partners were asked by the Gaming Control Board to provide a full accounting of their ownership.” “Adler failed to appear before the Gaming Control Board and lost his license.” (The Roots of Reno, p. 205.)

In 1956, news outlets reported that the Internal Revenue Service was after Adler for $400,000 in back taxes from the casinos.

Cal Neva Lodge, Inc., failed to report from $700,000 to $900,000 in income during fiscal years 1953, ’54 and 55.

Reno Gazette-Journal, Oct. 1, 1956.

[E]ach Summer Sanford D. Adler, president of Cal Neva Lodge, inc., would ask for an estimate of profits at Club Cal-Neva, in Reno, then would adjust the percentage, so that the Lodge losses at the lake would counteract any profit at the Reno club, so that the corporation which included both the Reno and Lake Tahoe casinos, would have not taxable income.

Internal revenue agents seized the money in Club Cal-Neva to settle claims Nov. 11, 1955, and the club closed immediately. A petition in bankruptcy was filed by the corporation next day, and Adler said that he would never engage in gambling in Nevada again. Both the lodge at the lake and the club in Reno have been sold, and are now under new management.

California Country Club Estates’ Merchant Builder (1951-1955)

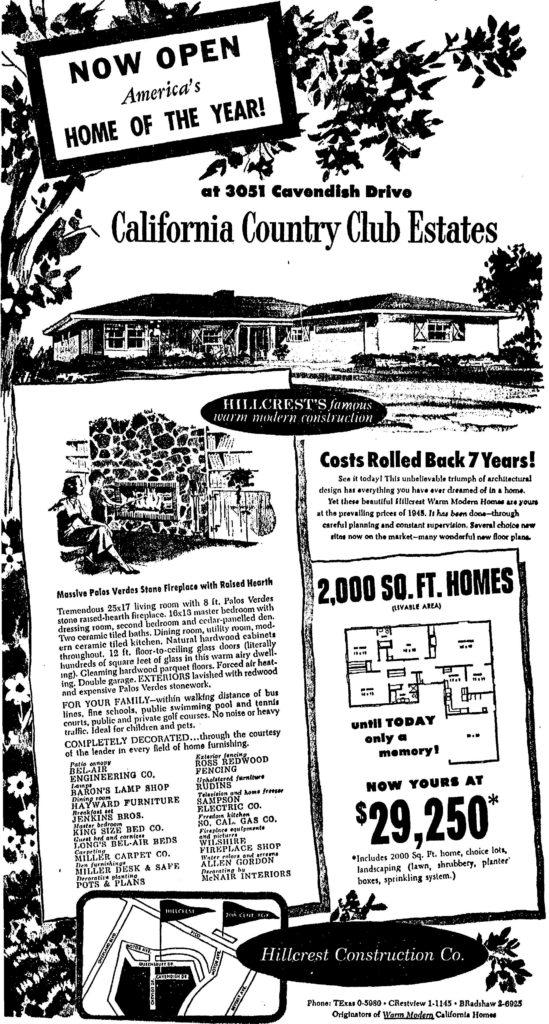

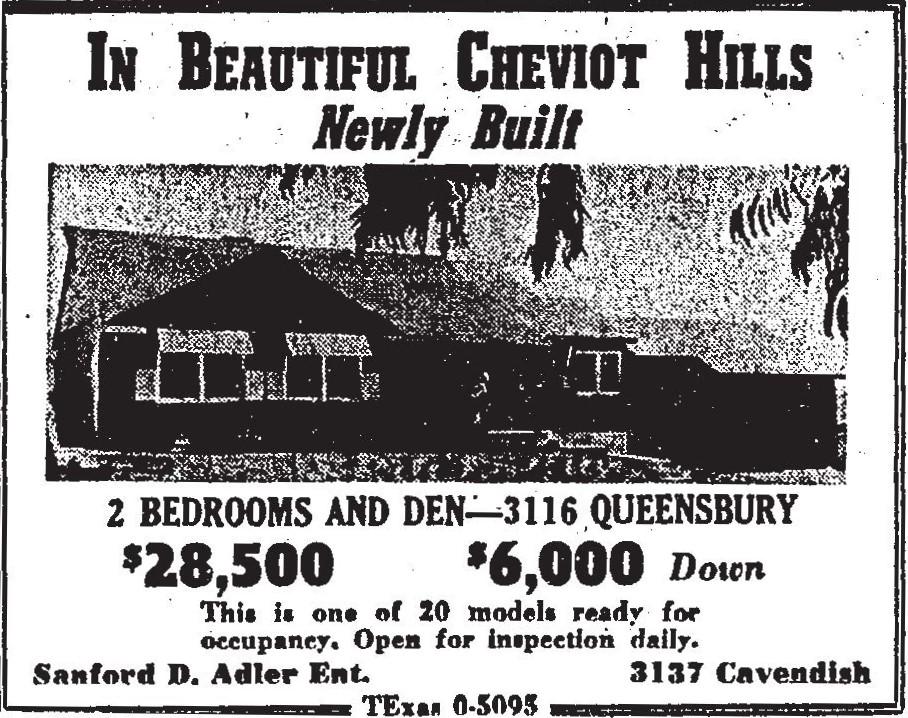

The Santa Monica Freeway was a decade off, and Southern Pacific’s Santa Monica Air Line passenger service was infrequent (and would end in 1953), so the below (June 8, 1952) advertisement said that homes were “within walking distance of bus lines.” Also, since the private Rancho Country Club had become the public Cheviot Hills Recreation Center in 1949, he touted its “public swimming pool and tennis courts.”

The Los Angeles Historic Resources (SurveyLA) gives some of the same background about the developer as is found here – in part because they relied on pages from an earlier version of this website and assistance from its author:

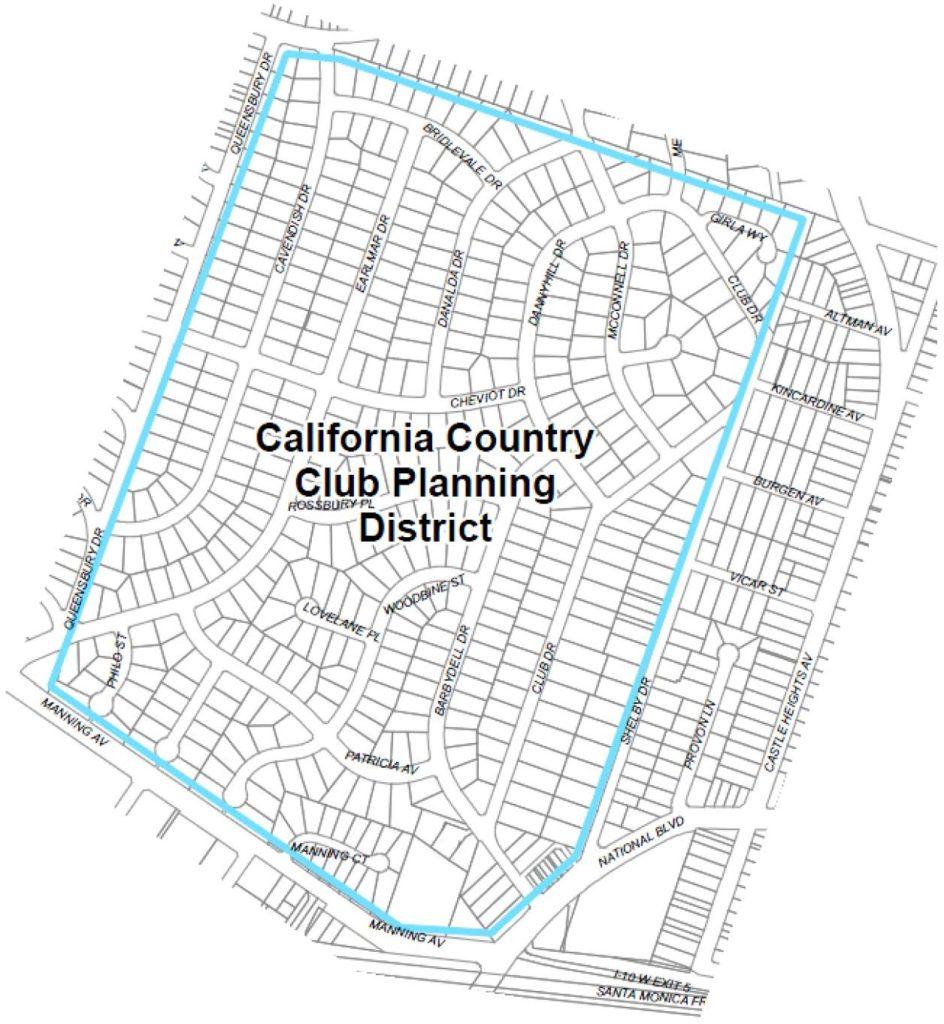

The California Country Club Planning District is a good example of the work of a merchant builder of mid-century era residential properties in West Los Angeles. It is associated with Los Angeles merchant builder Sanford D. Adler. Adler was active in Florida and also developed a small tract called Northridge Living Conditioned Homes in the San Fernando Valley designed by modernist architectural firm Palmer & Krisel. His organization owned the Del Mar Hotel as well as other holdings. In 1951, Adler subdivided an approximately 100-acre portion of the California Country Club golf course, which had been developed by Harry Culver. The new California Country Club Estates consisted of 410 Ranch-style single-family residences, which were initially sold from 1952 to 1955. Around the same time, the California Country Club Homes Association (still in operation today) was created to maintain restrictions and construction standards. Appealing to individuals with middle class incomes who worked in the entertainment industry, the California Country Club Estates development – then valued at $15,000,000 – was sold out by 1955.

The Los Angeles Historic Resources (SurveyLA) calls the California Country Club Estates neighborhood a “good example of a residential subdivision from the mid- 20th century”:

The district encompasses two adjacent residential tracts, both of which were subdivided in 1957. Both of the subdivisions were developed by Sanford D. Adler, a seasoned builder who had developed several other postwar tracts around the Valley. Adler collaborated with architects Dan Saxon Palmer and William Krisel, well-known for “bringing Modernism to the masses” by incorporating features associated with high-style Modernism into mass-produced tract housing. Palmer and Krisel designed the houses within Adler’s development, which consisted of four basic plans with a variety of décor packages and exterior finishes that produced a cohesive yet diverse collection of houses.

Los Angeles Historic Resources (SurveyLA), California Country Club Planning District.

Ads by the Hillcrest Construction Co. for the tract depicted a Ranch-style house with a low-pitched roof, decorative shutters, and a garage projecting toward the front of the property. The typically 2,000-square-foot houses priced at $29,250 featured “Hillcrest’s famous warm modern construction.”

The topography ranges widely from generally flat to mildly hilly, and many of the front yards slope down toward the street. One- to three-foot retaining walls clad with stone or brick are common. The street pattern is a mixture of curvilinear and orthogonal forms that create irregularly shaped blocks and impart a quiet residential character to the area. Consisting of approximately 138 acres, the approximately 475 district parcels range from rectangular to irregular in shape and are generally somewhat larger than those in the surrounding tracts. Traditional custom Ranch-style houses are typical of the neighborhood, many with wood board-and-batten siding, exposed rafter tails, brackets, and dovecotes. However, many individual residences have been altered with an additional story and non-original stone or stucco cladding. The wide streets, large lots, sidewalks, and setbacks give the neighborhood an open, spacious feel. Attached garages and driveways dominate the front elevations throughout the district. Original features of the tract include streetlights with cast iron posts and mass plantings of mature street trees, such as ficus and palms, which line various streets. The period of significance is 1952 to 1955.

Many of the houses have been enlarged with the addition of a second story, and the original wood and brick cladding has sometimes been replaced by stone, stucco, or clapboard. These alterations impact the overall integrity of the neighborhood, and therefore it does not appear to be eligible for listing as a historic district. However, many of the houses retain the original wood board-and-batten siding, exposed rafter beams, porch brackets, diamond-pane windows, and dovecotes. The spacious feel of the 1950s-era development oriented toward the automobile with its wide streets and prominent garages and driveways is retained. Moreover, original features of the tract such as streetlights with cast iron posts and mature street trees remain. Therefore, the district may warrant special consideration in the local planning process.

Northridge’s Living-Conditioned Homes (1957-1959)

Sanford Adler’s best-known development may be his “Living-Conditioned Homes” in Northridge, California.

The Living Conditioned Homes district is unique in that it is the only Palmer and Krisel tract in the San Fernando Valley to exhibit the flamboyant characteristics most commonly associated with their “Alexander-style” developments in Palm Springs and Las Vegas. Houses within the district exhibit degrees of architectural detail and expression that are not often seen in neighborhoods composed of mass-produced tract housing.

Los Angeles Historic Resources (SurveyLA), Northridge Report.

Architectural historian Sian Winship, in her 2011 master’s thesis, discusses Adler’s involvement the Living-Conditioned genre:

Of the expressive modern developments, one of the most interesting is Sanford D. Adler’s Living Conditioned Homes (1957-1959). Palmer and Krisel had previously worked with Adler and his son-in-law [Morton G. Rodin (1924-2009] on Storybook Village (1956), a predominantly contemporary Ranch-style development in Northridge. Because of the two recessions during the decade, developers increasingly turned to architecture to differentiate their products. So, for their next project together, Krisel persuaded Adler’s son-in-law to try a comprehensively avant-garde Mid-Century Modern development (see Figure 6:3), Living Conditioned Homes (1957-9).

Sian Winship, Quantity and Quality: Architects Working for Developers In Southern California, 1960-1973, (2011) pp. 201-202.

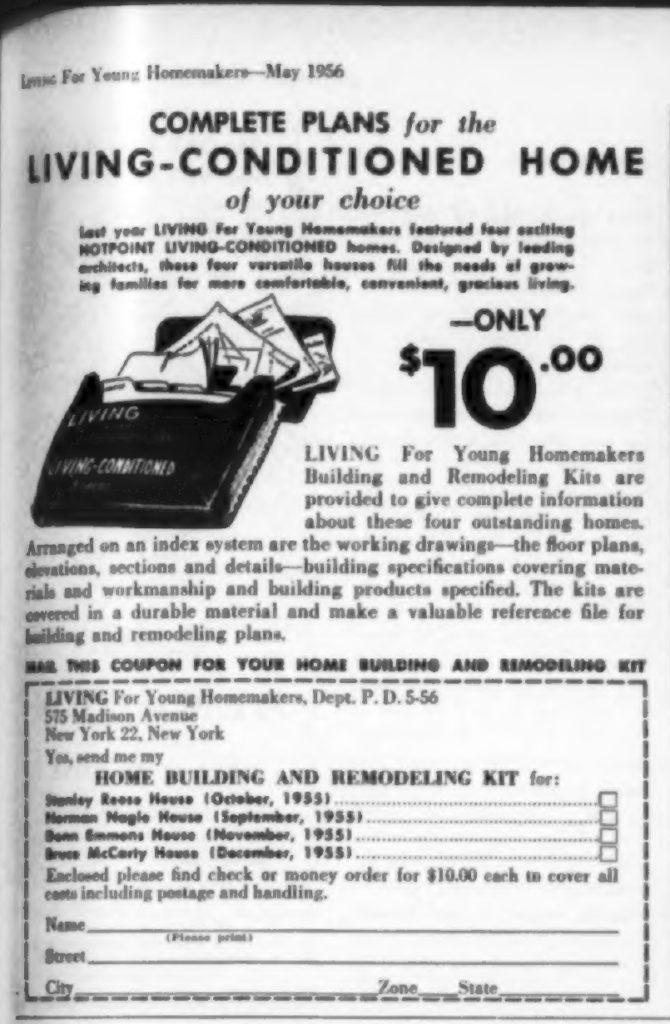

The idea of the “Living Conditioned Home” appears to have originated in 1955 with the magazine, Living for Young Homemakers. A shelter magazine eager to capitalize on the advertising, merchandising and promotional opportunities associated with the display home, the magazine identified a series of “Hotpoint Living Conditioned” homes for tour in several markets around the country. The homes were meant to be “architecturally indigenous to the particular region in which [they were] built,” and feature six aspects of “Living Conditioning:” light, sound, climate, safety, space, and color. The magazine continued the promotion annually. In 1956 and 1957, in an effort to broaden the appeal of the promotion to advertisers and in-kind donations, the sponsors became local/regional energy companies and the term “Electri-Living” was added to the promotion. Between May and September 1955, the furnished display homes were toured by 3 million people. Styles for the homes ranged from avant-garde modern, to contemporary and traditional ranch.

It is not known how Adler and his son-in-law became acquainted with Living for Young Homemakers magazine, but in 1957 they teamed with the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power to create a tract of “Living Conditioned Homes.” These homes were marketed aggressively using the magazine’s endorsement and their concept of six types of “Living Conditioning.” It is quite likely that the idea came from Krisel and Palmer’s marketing and publicity man, David Parry. Parry is credited on the sales brochure and graphics (see Figure 4:22) for Living Conditioned Homes and the level of integration in the advertising, publicity and collateral materials demonstrates a sophisticated marketing hand. Parry would have also been well positioned to know of the magazine’s program and view it as a way to leverage publicity. The concept of different types of “Living Conditioning” also is evocative of the types of message points that Parry was coaching Palmer and Krisel on with the “psychological-based design” and “introvert and extrovert plans” discussed previously.

Sian Winship, Quantity and Quality: Architects Working for Developers In Southern California, 1960-1973, (2011) pp. 202-203.

The term “Living-Conditioned” is associated with the concept of living-conditioning, a progressive homebuilding initiative that was sponsored in the 1950s by “LIVING for Young Homemakers” magazine.

Los Angeles Historic Resources (SurveyLA), Northridge Report.

Adler’s development in Northridge appears to have been the fullest expression of the initiative’s goals and objectives. Development within the tract began in 1957 and continued through 1959.

The Living-Conditioned Homes Residential Historic District contains an excellent concentration of Mid-Century Modern residential architecture in Northridge, designed by noted Los Angeles architects Palmer and Krisel. It is also significant as an innovative example of post-World War II suburbanization, espousing the principles of a progressive homebuilding initiative known as “Living-Conditioning.” The period of significance has been identified as 1957-1959, accounting for the district’s period of development, and 72% of properties contribute to its significance.