Don José de Arnaz’ Los Angeles County Ranch

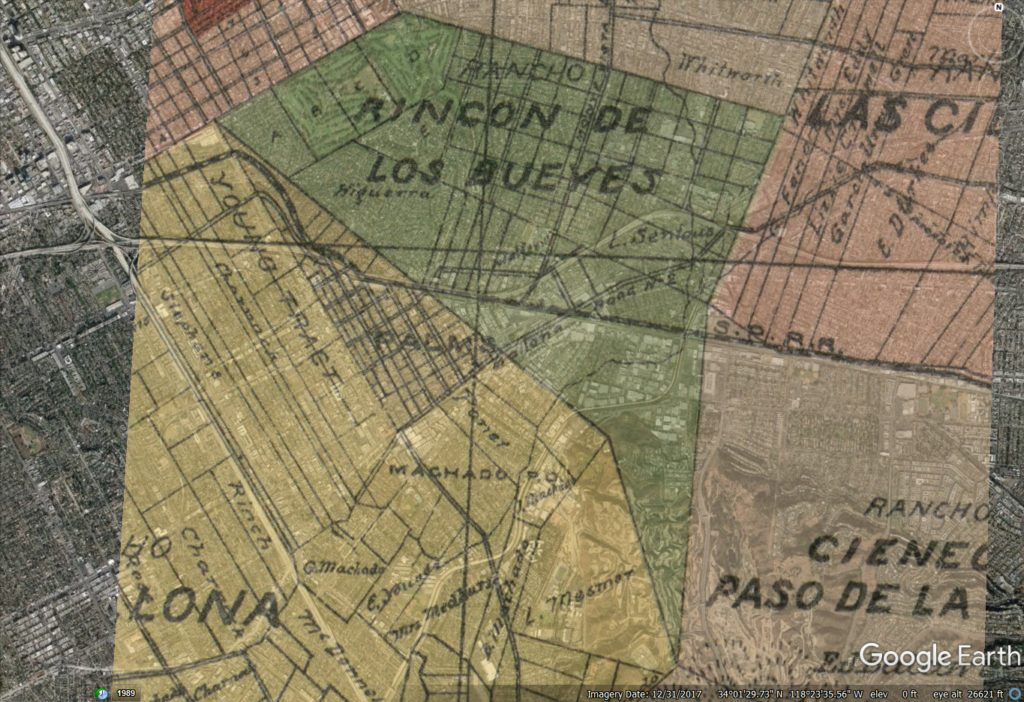

In the mid to late-Nineteenth Century, Don José de Arnaz carved a two and a half square mile ranch from the old Rancho Rincón de los Bueyes in what would be West Los Angeles in the century to come. After he passed, the land was held by some of the Los Angeles area’s wealthiest families: the Rindge family, who owned Malibu, and the Manuel Dominguez clan, who owned (and still own) a swath of the South Bay. Over time, Arnaz’ ranch would have orchards, vineyards, barley fields, oil wells, private schools, golf courses, a creamery, and a movie studio backlot where Laurel & Hardy played fools and the Little Rascals played. Still, as late as 1939, one half square mile of the Arnaz Rancho was farmland. Nearly all of these would yield to suburban homes and associated stores and services; two golf courses remain. In 1949, the county district of “Arnaz” (already homes) was incorporated into the City of Los Angeles, all but wiping away Don José’s 100-year imprint on the land.

1849-1872 – Don José Buys Parts of Rancho Rincón de los Bueyes and the U. S. Government Confirms Higueras’ ownership (1849-1872)

On February 2, 1848, Rancho Rincón de los Bueyes became part of the United States as spoils of the Mexican American War. Under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, grantees and their successors were to retained ownership of their land, though they would have to prove the validity of their Spanish and Mexican grants before a United States commission. Arnaz already had a home with an orchard and Vineyard in Los Angeles in 1848; Colonel Jonathan D. Stevenson looted and burned it in 1848. (Recuerdos.) However, as can be seen in his biography, through at least the 1870s, Arnaz’ primary interests were in what is today’s Ventura County.

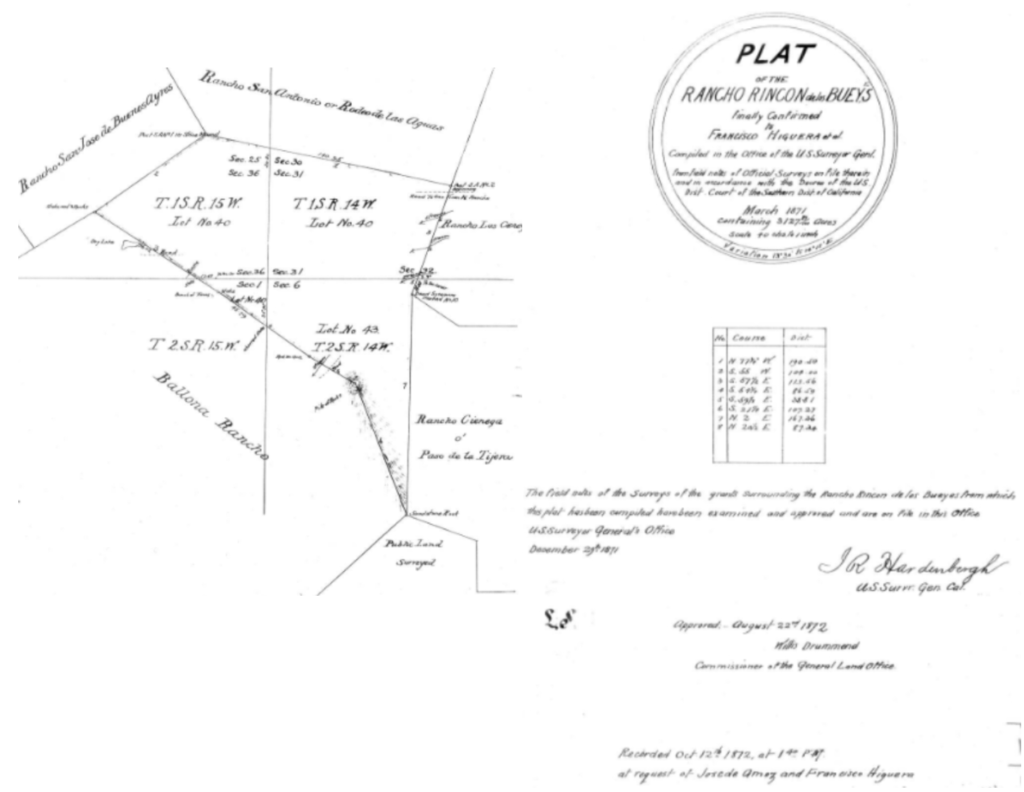

After the United States’ takeover, José de Arnaz bought parts of the Rincón de los Bueyes from a grantee’s sons, Secondino and Francisco Higuera, who owned it jointly: in 1849, Arnaz bought Secondino’s undivided half-interest, and, in 1867, he bought Francisco’s. What remained was to clear Arnaz’ (and others’) title before the board of land commissioners appointed “to ascertain and settle the private land claims in the State of California” by an Act of Congress on March 3, 1851. (9 Stat. 631.) It was not a simple process.

The sales, however, could not be considered as final until the Higueras had proved their claims before the United States Land Commission. From 1852 until 1869 they, aided by the influential Arnaz, fought to hold the rancho. The litigation was complicated by the fact that squatters had moved in on parts of the land. Descendents of these squatters became social and business leaders of Los Angeles. Arnaz always carried a rifle, and used it in more than one instance, finally evicting most of the squatters from the land and clearing the title. The patent was eventually issued August 27, 1872.

Romance of a Rancho (The Beverly Hills Citizen, Volume XVII – No. 2, June 23, 1939)

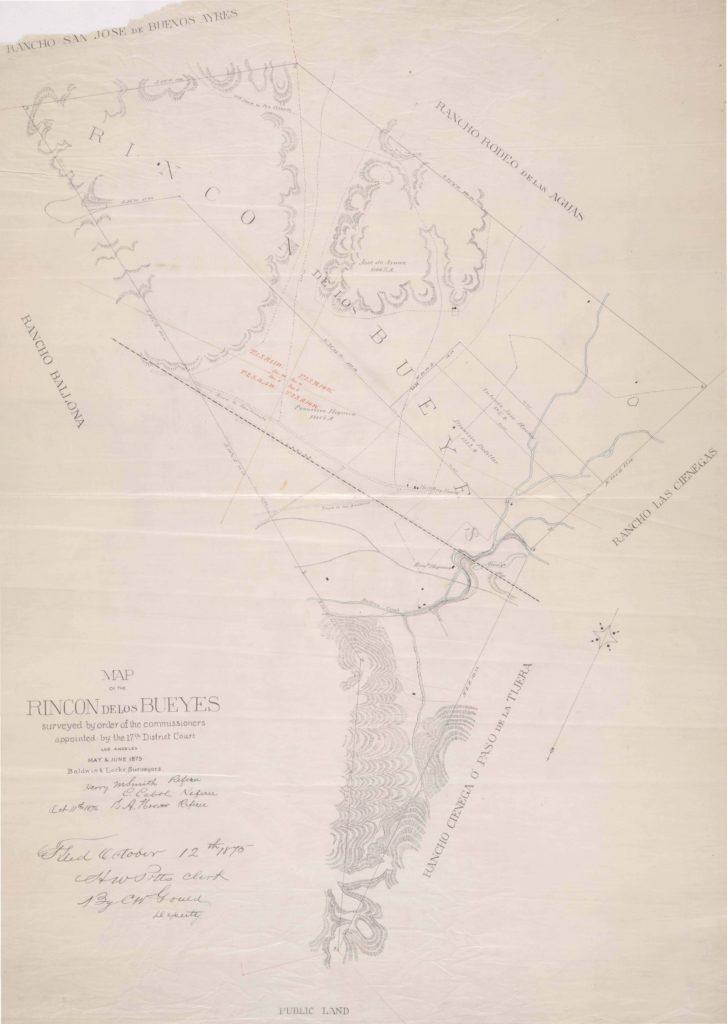

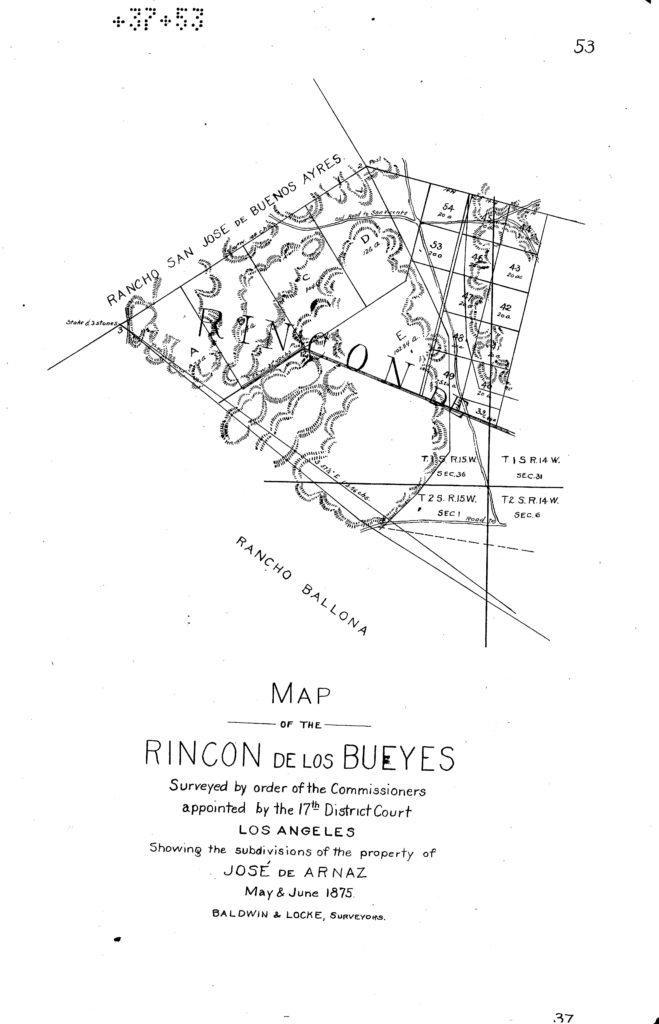

1875 – Survey Divides Rancho Rincón de los Bueyes between Arnaz, Rocha, Botiller, and Francisco Higuera

With the original land grant confirmed, it remained to clarify the interests of those who claimed interests in it – whether squatters, purchasers, or putative owners. W. W. Robinson’s Culver City, A Calendar of Events give the following details.

Januario Avila (1810-1872) testified in 1852 that, when he first knew it, the Rancho was occupied by Spain’s grantees, Bernardo Higuera (1790-1837) and Cornelio Maria Lopez (1792-1850). He recalled that Cornelio Lopez abandoned it while Bernardo built two houses on the land in about 1822 or 1823, and lived out his life there. After Bernardo Higuera died in 1837, his children Jose Secondino Higuera (1822-1880) and Francisco Maria Higuera (1823-1903) lived there.

Another version has Bernardo “verbally” ceding his interest to his brother Josef Policarpio Higuera (1799-1842). Along those lines, in 1834, Bernardo’s brothers Josef Policarpio Higuera and Mariano Higuera (1804-1875), Bernardo’s son Francisco, and Pedro Mendez, claimed title “denouncement,” saying that Bernardo had abandoned the ranch. Apparently, they relied on an 1836 census showing Bernardo and his wife, Maria Rosalia Palomares (1804-1850), living in the City of Los Angeles. (The Rancho would not be within Los Angeles city limits until, at least, 1923.)

Pedro Mendez was apparently not a family member, but Francisco Botiller (Boutillier) (1819-1909) said Pedro Mendez “lived on the rancho with Policarpio.” Botiller further related that, after Policarpio’s death, Mendez sold the small house he had on the place to Policarpio’s widow . . . .”

Robinson’s “Calendar of Events” also notes those who used, but did not make claims to, Rincón de los Bueyes: Vicente Sanchez allowed hogs to pasture on the Rincon in 1843 and brothers Felipe Talamantes (1772-1856) and Tomas Talamantes (1793-1875) lived on the Rincon de los Bueyes – though they owned neighboring Rancho Ballona.

José Antonio Rocha II

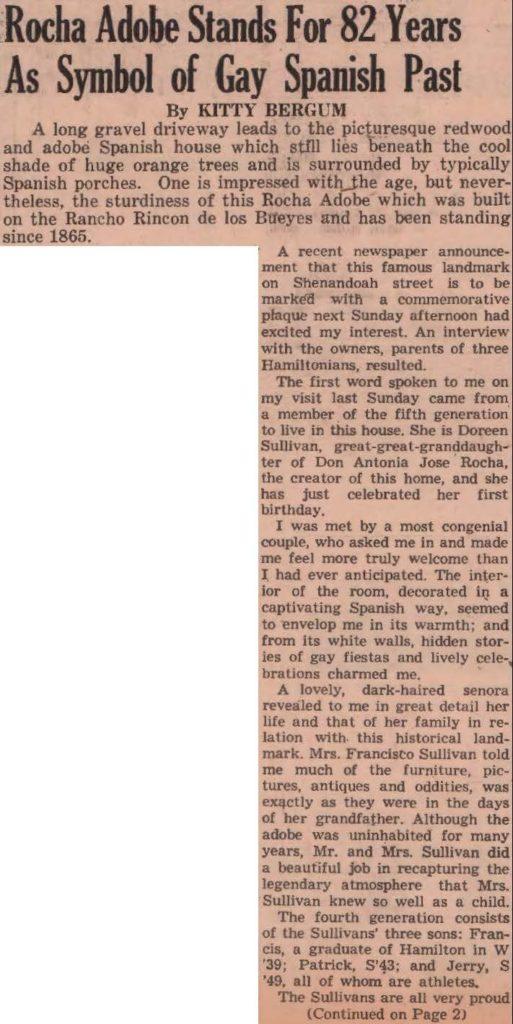

José Antonio Rocha II (1825-1908) was one of those with a straightforward interest in the Rancho Rincón de los Bueyes, having purchased a portion from Francisco Higuera. His family home remained on the Rancho well into the 20th century – and possibly beyond.

Francisco Higuera conveyed 100 acres of Rincon de los Bueyes to Jose Antonio Rocha II on November 8, 1872. It was on this tract of land that Rocha constructed the adobe standing today on Shenandoah Street. Apparently, he settled in the area years before the land formally became his estate, because he built his house there in in 1865 [Historic American Buildings Survey says approximately 1872].

José Antonio Rocha II was the son of José Antonio Rocha, a Portuguese sailor who jumped ship in Monterey in 1815. His mother was Josefa Alvarado, a lady of Spanish ancestry. He was one of five children. The elder Rocha came to Los Angeles and opened a blacksmith shop. One of the pueblo’s most distinguished citizens, Rocha became the grantee of Rancho La Brea. This 4,439-acre grant was located a few miles west of the pueblo of Los Angeles. In 1836, the Rocha family moved to Santa Barbara. José Antonio Rocha II eventually returned to Los Angeles where he served as the county assessor and a Justice of the Peace.

Although Rancho Rincon de los Bueyes was subdivided multiple times, members of the Rocha family still held a part of the 100-acre tract, which included the adobe. Gradually, the rich farmland in the area developed into a bustling metropolis. Much of the area was annexed to the city of Los Angeles on May 22, 1915, as part of the Palms District. For many years the Rocha adobe was left abandoned until a descendant of the Rocha acquired it as a residence. It was restored in 1979.

“Things to Do in Los Angeles”

– archived at Internet Archive Wayback Machine.

Today, this large squared house of adobe and wood stands away from the street on its own private lane. It retains much of the original construction. The adobe walls of the lower level are twenty-three inches thick. Original adobe bricks can be seen on the west side of the structure. The house is surrounded on all sides by roofed porches what the Spanish called corredores. The upper story is built of redwood ship siding and the roof is wood shingled. Dormer windows on the second story are a later addition. Inside, there is what Jose Antonio Rocha II called his “gringo” stairway leading to the upper level. Most early adobes with two stories had outdoor staircases. Interior stairways were fashionable in the latter part of the 1800s, when Yankee craftsmanship influenced adobe construction. The Rocha adobe is a private residence and is not open to the public.

“Things to Do in Los Angeles”

– archived at Internet Archive Wayback Machine.

Antonio Ricardo Rocha (1866-1936), shown below, lived his entire life in the Rocha Adobe built by his father, Antonio Jose Rocha, II (1825-1908). Both would have known Arnaz.

In 1875, a court divvied up Rancho Rincón de los Bueyes, with Arnaz and Francisco Higuera getting the bulk. The map below shows José de Arnaz with 1506.23 acres in the northern portion, Francisco Higuera, 1355.1 acres in the southern portion, Dionisio Botiller (1842-1915) with 172.9 acres, and Antonio Jose Rocha II with 88.75 acres (both in the middle and eastern sections). The Los Angeles Herald reported on April 2, 1875, “An interlocutory decree entered awarding to plaintiff [José de Arnaz] an undivided one-half of land in controversy, less 250 acres to defendant Rocha, 100 acres to defendant Dionisio Botiller and 200 acres to defendant Higuera.” (L.A. Herald, April 3, 1875, Court Reports, Arnaz vs. Higuera.) Dioniosio was Francisco Botiller’s nephew and also on Los Angeles’ common council.

1885 – Arnaz’ Ranch House Built

Romance of a Rancho tells of Arnaz moving back to Los Angeles: “when litigation in connection with Rancho Rincon de los Bueyes was finally settled,” which was in 1875, as described above.

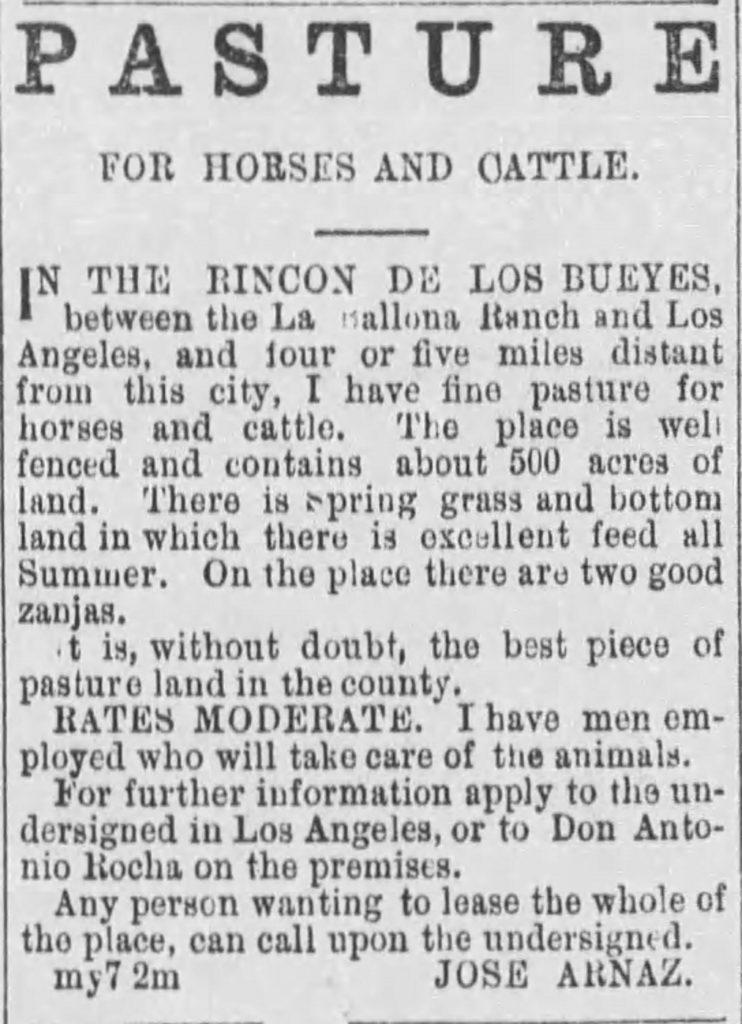

In May – July 1878, José de Arnaz advertised pasture for horses and cattle on his “about 500 acres” of “well-fenced land” with “two good zanjas” and “Spring grass and bottom land in which there is excellent feed all Summer.” Those interested were directed to see him in Los Angeles or his neighbor, “Don Antonio Rocha on the premises.” (L. A. Evening Express, June 27, 1878.)

Thereafter, Don José built his “15-room house which became a showplace.” (Romance of a Rancho.) In 1886, he hosted a housewarming, which also marked the sixteenth birthday and coming out party for his daughter, Prexcedes. He “invited everybody from what is now Western avenue to the sea. Over 200 guests sipped his wines and danced throughout the night.” (Romance of a Rancho; Ancestry.com puts the daughter’s 16th birthday on Saturday, October 16, 1886.)

Pioneering Lima bean farmer

José de Arnaz may have initiated the commercial growth of Lima beans in North America. One history claims that, in 1868, Virginia-born Henry Lewis (1837-1906) “planted the first lima beans ever put into the soil of the United States” on his 109 acres near Carpinteria (Ventura County). The story goes that Lewis’ friend obtained them from a sailor on a ship anchored at Santa Barbara after a recent voyage from Lima Peru. (Charles Monford Gidney, Benjamin Brooks, Edwin M. Sheridan, History of Santa Barbara, San Luis Obispo and Ventura Counties, California, (1917), p. 619.) At least part of that history is untrue: Lima beans were “put into the soil of the United known” at least 50 years earlier, since “George Washington sent a letter to Anthony Whitting in February of 1793 regarding lima beans that Mrs. Washington wanted the gardener to plant.“

Unlike Mr. Lewis, Arnaz had access to the Peruvian beans as early as 1840. In those years, Don José was supercargo on the Clarita, one of the ships operating out of Peru’s primary port city. In his words, “The company always kept one of its vessels on the coast with merchandise while the other carried the harvest of California – that is, tallow – to Callao, to be sold in Lima.” (Recuerdos.)

Indeed, other Ventura County histories have Arnaz as “seeding” the Lima bean industry:

Don Jose de Arnaz brought lima beans home with him from one of his voyages of trade down the coast of South America. He planted the beans from Lima, Peru, in his home garden. It was a special event when his family had their first meal of these new delicious beans. He proudly showed his beans to his friends and gave them some to raise in their gardens.

Later, in the 1860s, Mr. W. L. Lewis, of Carpinteria, planted more lima beans than he could use for his own family. He found that there was a market for this food which could be eaten fresh from the garden or dried.

For over thirty years the bean industry led all other industries in [Ventura] county.

Anna Mae Davis, A Fourth Grade History of Ventura County, Master’s Thesis (Aug. 1950), pp. 108-110, citing E. M. Sheridan, “The Story of Rancho Arnaz,” (Unpublished article in Ventura City Library), p. 6 and Sol N. Sheridan, A History of Ventura County, I, 367. See also David “Mr. Ojai” Mason (1939-2017), “Arnaz was a Merchant, Doctor and Rancher”: Arnaz “planted the first field of wheat and raised the first crop of lima beans in Ventura County.”

When Arnaz’ Los Angeles County ranch was sold, in 1905, a report said “Lima beans and barley are among the crops raised, and about thirty acres of the tract are in a thirteen-year-old vineyard.” (L. A. Evening Express, July 1, 1905.) In 1939, just before the ranch’s demise, it was reported that over 300 acres of the 330-acre farm were planted in lima beans. (Romance of a Rancho.)

1889 – José de Arnaz’ Subdivision

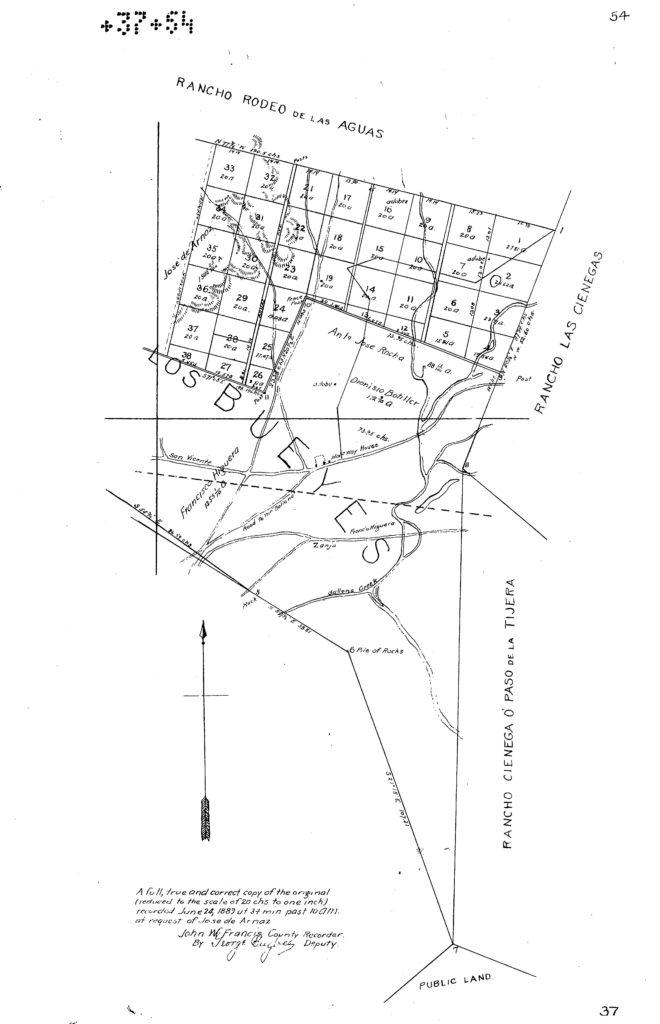

The following map (displayed in two parts, west and east) “recorded June 24, 1889 … at the request of Jose de Arnaz” shows Arnaz’ subdivision of the 1506.23-acre Arnaz Ranch on Rancho Rincón de los Bueyes. The larger lots (A through E) of hilly land to the west had parcels ranging between 73 and 126 acres. The smaller lots, on flatter land to the north and east, were generally 20 acres. The road between lots 32 and 21 is Arnaz Avenue, renamed Robertson Boulevard in 1926. The road to its immediate west was Anguisola Avenue, which was vacated in 1906.

January 1887 – Arnaz Children Sell Half-Interest to Wick & Ward

In January 1887, Manuel, Eduardo, José Maria, and Maclovio sold half of their interest in Rancho Rincon de Los Bueyes (along with half their interest in Ranchos San Jose and the San Jose addition) to Moses “Moye” L. Wicks (1855-1932) and Shirley C. Ward (1861-1929). This author does not know the terms of the sales.

Wicks and Ward were partners in a law firm by that name. Wicks, who had been a judge, writer, and newspaperman, may be best remembered as the promoter of Port Ballona – sort of an ancestor of Marina del Rey. “On August 21, 1887, the railroad was finished and the first train brought an excursion load of three hundred prominent Angelenos to Port Ballona. . . .. The boom burst in 1888, the funds of the Ballona Harbor and Improvement Company became exhausted, the sands and the tides continued their opposition — and the dream of Port Ballona remained a dream.” (W. W. Robinson, “Culver City, California: A Calendar of Events (1939).) Ward, was eulogized as active in business and civic affairs, involved in real estate, and a power in the oil business. He should also be remembered as “Special U. S. Attorney for the Mission Indians” in Byrne v. Alas, 16 P. 523 (Cal. 1888), advocating for Native Americans’ right to remain on land where they resided.

February 1887 – Don Jose Sells Half Interest to Others

In February, 1887, Don José sold lots A, B, C, D, and E to Joseph Moffatt and H. Clay Graham for $25,450. (L. A. Times, Feb. 6, 1887.) In March 1887, Moffatt sold his undivided 1/6th interest to James Janes for $2500. (L. A. Times, Mar. 16, 1887.) In September 1887, Graham is shown buying Lots A-E from Frank W. Cherry for $3000. (L. A. Times, Sept. 2, 1887.)

1896 – Heirs of José de Arnaz’ First Wife, Maria Mercedes de Abila, Get Western Portion of the Ranch and Sell

Don José de Arnaz died on February 1, 1895. The next year, on April 25, 1896, a court divided Lots A, B, C, and E of the Arnaz ranch (the western, hilly land) among the children/devisees of the late Don José and his first wife, Maria Mercedes de Avila (1832-1867), according to her will and his will. Romance of a Rancho details the division:

Before his death at the age of 74, on February 1, 1895, Don Jose had drawn a will dividing his rancho into two parts. He drew a line bisecting the rancho approximately north and south, along the eastern boundaries of what today is the Hillcrest Country Club. All west of this line went directly to surviving children by his first wife; all lying east of the line went to his widow to be held in trust for herself and her surviving children. …. They received shares varying from 80 acres to 200 acres, depending upon the value of the land, whether it was level or hilly, watered or dry. These shares, totaling over 1000 acres, they disposed of at different times to different parties.

Mercedes’ heirs disposed of their remaining interest in the Ranch soon after the April 1896 partition. On May 21, 1896, Merced Abila’s inheritors conveyed Lot E for $4500 (about $44 per acre) to Arthur F. Gilmore (1850-1918). On May 27, 1896, Gilmore got Lot A for $3640 (about $35 per acre); Lot B for $3640 (about $35 per acre); and on July 29, 1896, Lot C for $4700 (about $45 per acre). (In 2023 dollars, the price per acre ranged from about $1,265 to $1,625.) The buyer, Arthur Gilmore, was a dairy farmer who had struck oil while drilling for water. His son, Earl B. Gilmore (1887-1964), developed Gilmore Oil Company. The family still owns Farmers Market at Third and Fairfax.

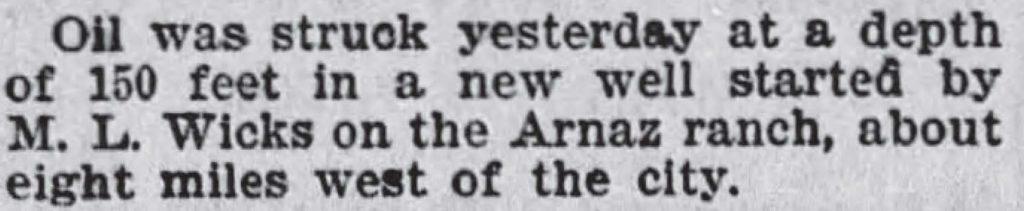

1900 – Oil Found under Arnaz Ranch

July 1905 – Gilmore Sells to Burkhard

In July 1905, Arthur F. Gilmore would sell Lots B, C, and E to the Burkhard Investment Company (a family corporation formed in 1912 by Joseph Heronimus Burkhard (1848-1928)) for about $200 an acre. Lot A now holds part of the Country Club Highlands tract. Lots B and C would become the bulk of today’s Cheviot Hills Recreation Center – after passing through a few more owners. Most of Lot E would make up the Monte-Mar Vista subdivision. Lot D and the northern portion of Lot E would hold the Hillcrest Country Club. Since Gilmore had become an oilman with the discovery on his other property, and with oil found on the Arnaz ranch in 1900 – after Gilmore’s purchase – it would be interesting to know if oil rights were part of Gilmore’s sale to Burkhard.

June 1905 – José de Arnaz’ Second Wife, Doña Maria Camarillo de Arnaz, and her Children Get Eastern Portion of the Ranch

On June 9, 1905, the Los Angeles Herald reported the partition of the eastern half of the Arnaz Ranch under the headline “Old Spanish Estate is Finally Settled”:

By a decision handed down by Judge Bordwell yesterday in the Arnaz case, the rancho Rincon de Las Bueyes, one of the finest pieces of farming property in the southwest, was finally distributed and a complete and amicable settlement made between the heirs of the late Don Jose de Arnaz, who died February 1 [1895].

The Arnaz property consists of about 800 acres of farming land on the electric line between Los Angeles and Santa Monica. The electric line cuts through one corner of the property, leaving 86 acres on the one side and a little over 647 acres on the other. When Senior [sic] Arnaz died, seven heirs laid claim to the property, which, according to court value, is worth $140,000, but which according to real estate men is worth a great deal more. At the same time, L. G. Olivaris entered action for $1500 mortgage on the property. John Wolfskill, John B. Arnesty and John B. Sanchez were appointed referees and their opinions formed the base of the decision given yesterday.

Attorney Thomas L. Wynder was allowed $3500 fee, and each of the referees was allowed $50.

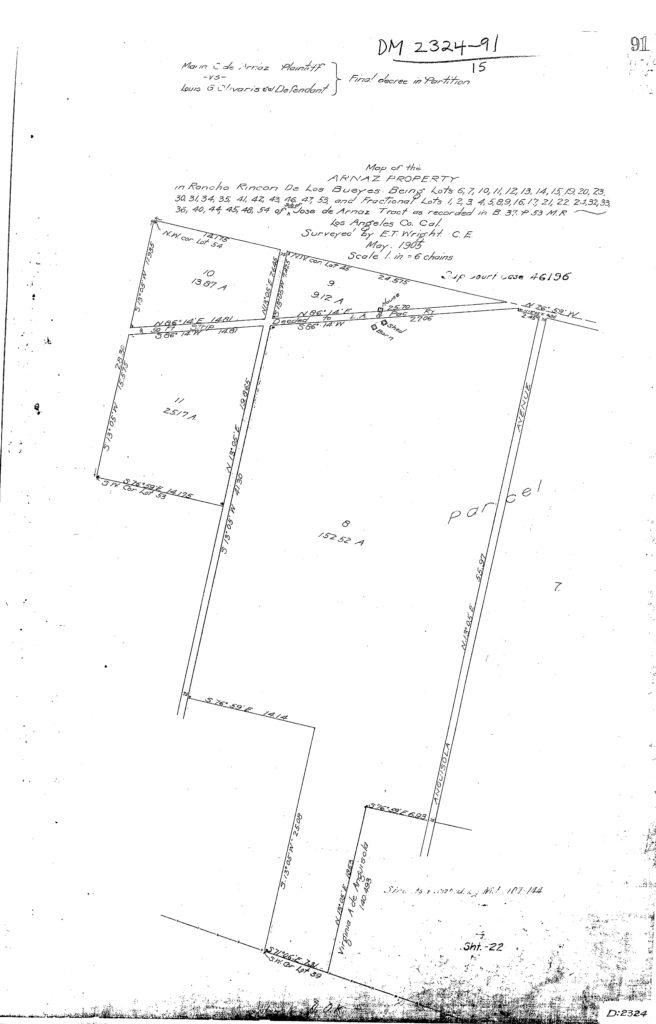

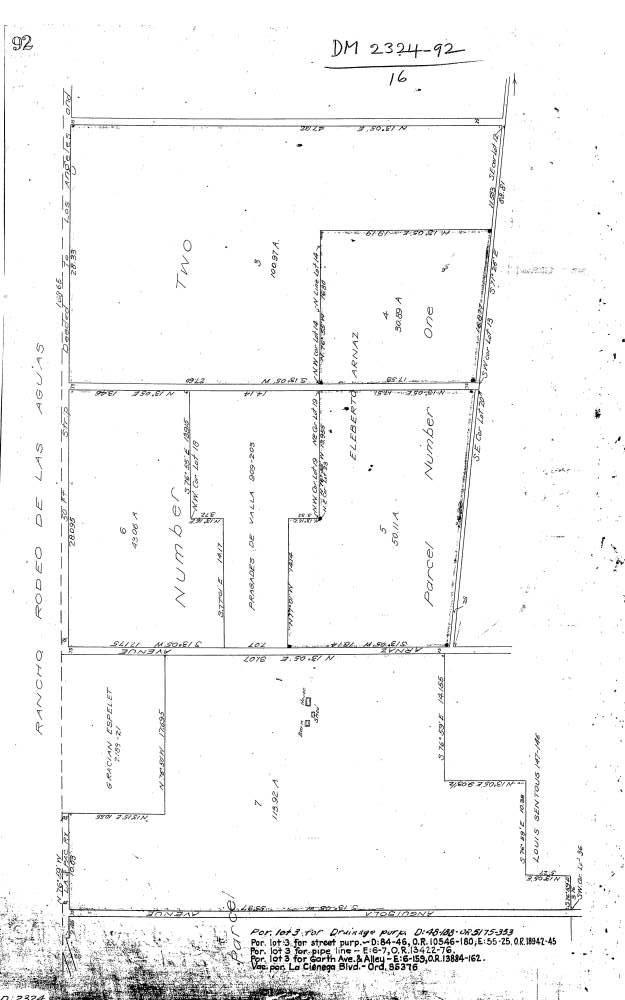

The Los Angeles Times gave these details on the partition case, entitled Maria C. de Arnaz v. Louis G. Olivaris.

Originally the Arnaz lands formed a part of the Rancho Rincon de Los Bueyes, and the widow was left an undivided seventh of the entire holding. In order to partition the estate it has been necessary for the referees to lay out a public road, so that all the heirs may have access . . .

The following three maps show the partitioned ranchland.

July 1905 – Eastern Portion of Ranch Sold by Arnaz’ Widow and Children

Like their half-siblings before them, Arnaz’ heirs by his second wife, Doña Maria Camarillo de Arnaz, largely waited for the land to be partitioned by a court before selling it. The process took ten years, over which Doña Maria “continued raising cattle, making wine, and growing grain, aided by a trusted foreman named Olvera.” (Romance of a Rancho.) She leased the “Portrero” (pasture) to Louis Olivaris (Dec. 13, 1900, L.A. Herald), who was party to the partition lawsuit, which concluded on June 8, 1905. With the partition complete, the heirs started selling.

“Romance of a Rancho” has the Rindge/Marblehead Land Company interests buying the Arnaz ranch in 1904. (“In 1904, with court approval, she sold the property to Mrs. Ringe for $125,000, of which the court awarded her $40,000, the remaining $85,000 being divided among her children in proportion to the value of the tracts Don Jose had set aside for them.”) The Los Angeles Times told the same story: “‘The new [Beverlywood] development was conceived more than a year ago when a syndicate of local investors acquired the noted Arnaz Ranch from the Marblehead Land Co., which had held ownership since 1904,’” Leimart explained.” (L. A. Times, June 2, 1940.) This writer has not located that 1904 sale, and it is unlikely that expensive/large a parcel was sold before the 1905 partition.

A more likely scenario is that on about June 25, 1905, Robert Conran “R. C.” Gillis (1864-1947) of the Santa Monica Land and Water Company bought the family out. “[O]ne of the principal land owners between Los Angeles and the ocean” bought the 625-acre Arnaz ranch “through Leo J. Maguire & Co. for Maria Carmarillo [sic] de Arnaz and her children, heirs of the late Don Jose de Arnaz.” (June 25, 1905, L. A. Sunday Herald.) A couple of days later, Gillis sold it for a tidy profit: “Edward F. Tripp and associates have paid R. C. Gillis $140,000 for the Don Jose de Arnaz rancho of 625 acres. …. Mr. Gillis bought the acreage last week for $125,000. The purchasers will subdivide and improve the property.” (June 27, 1905, L. A. Herald.) The sale’s historic significance was not overlooked: “The property was held for fifty years by Don Jose de Arnaz. It is the last of the old Spanish grants in the Cahuenga Valley …, and its transfer from the family by which it was so long owned to persons by whom it will be cut up into smaller holdings is necessarily an event of some prominence in the history of the valley in which the land is located.” (July 1, 1905, L. A. Evening Express.)

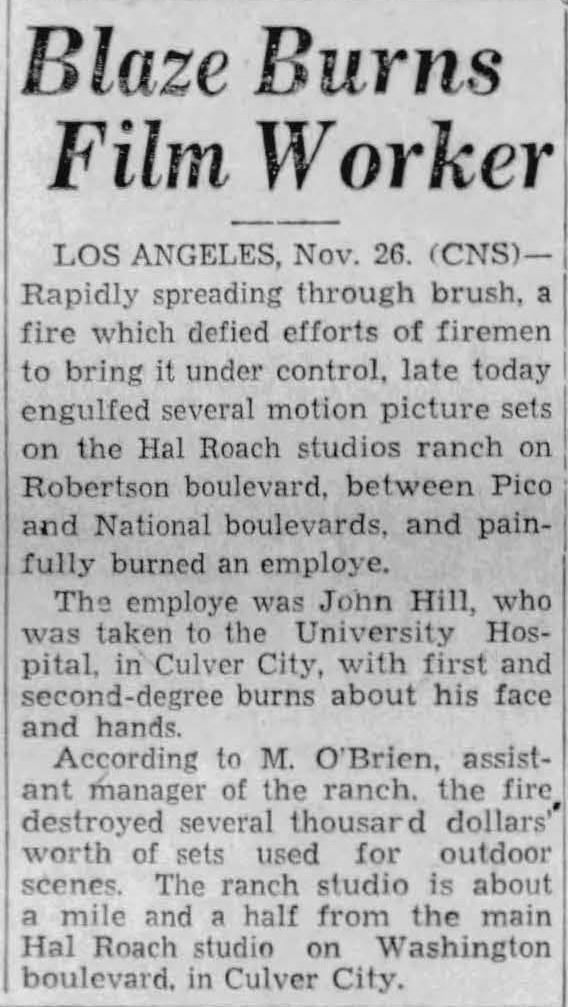

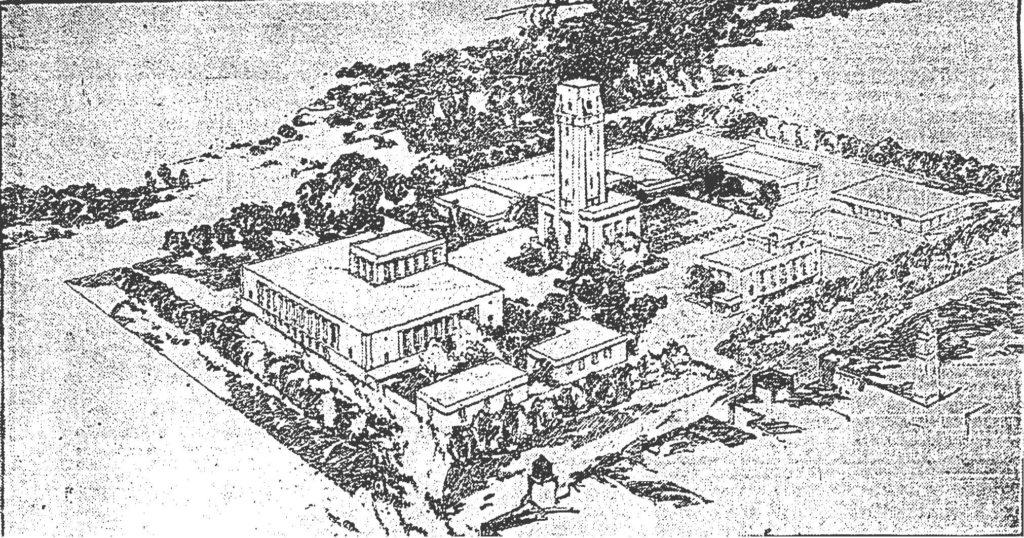

1923-1933 – Hal Roach Studios’ backlot: “Roach Ranch”

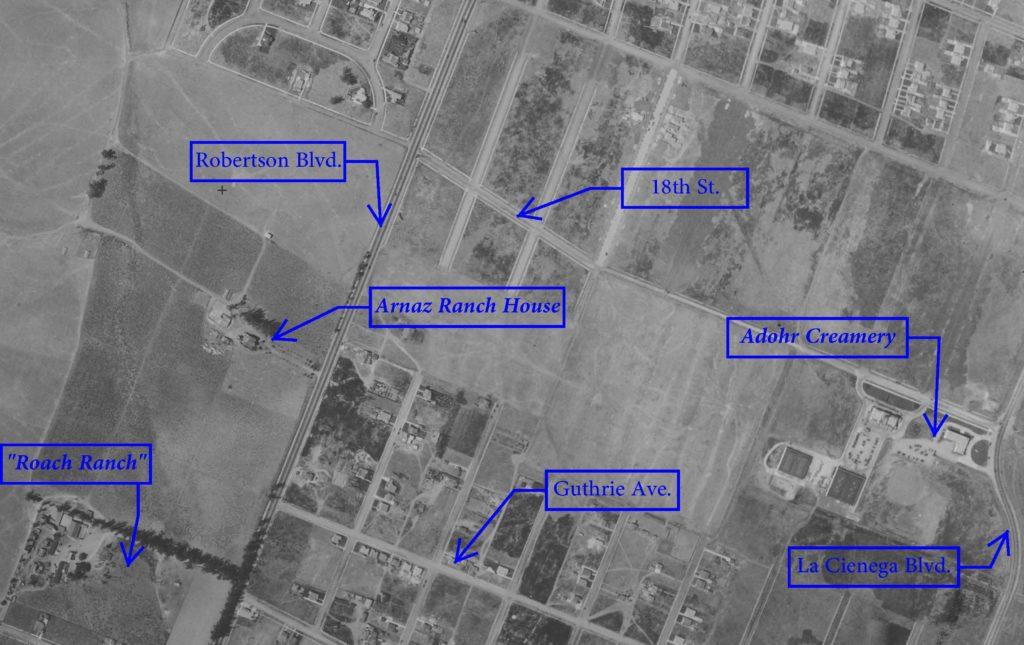

From 1919 until 1963, Hal Roach Studios, known as “The Laugh Factory to the World,” operated south of the Arnaz Ranch at Washington and National boulevards in Culver City. The studio made comedy films featuring Harold Lloyd (1893-1971), the Our Gang kids, and Laurel and Hardy, among others. (Stan Laurel (1890-1965) lived at 10353 Glenbarr Avenue in nearby Cheviot Hills from 1934-1938.)

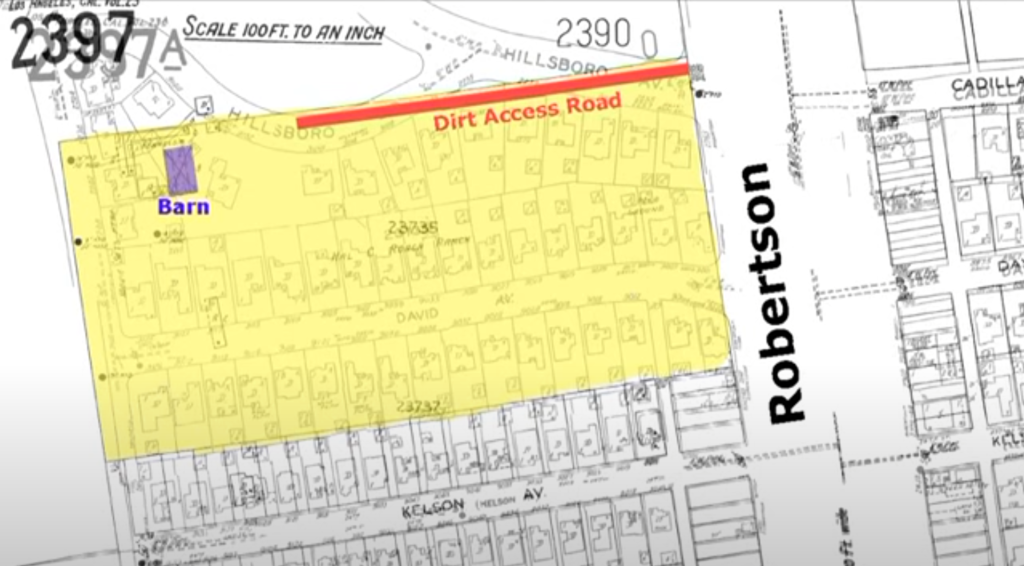

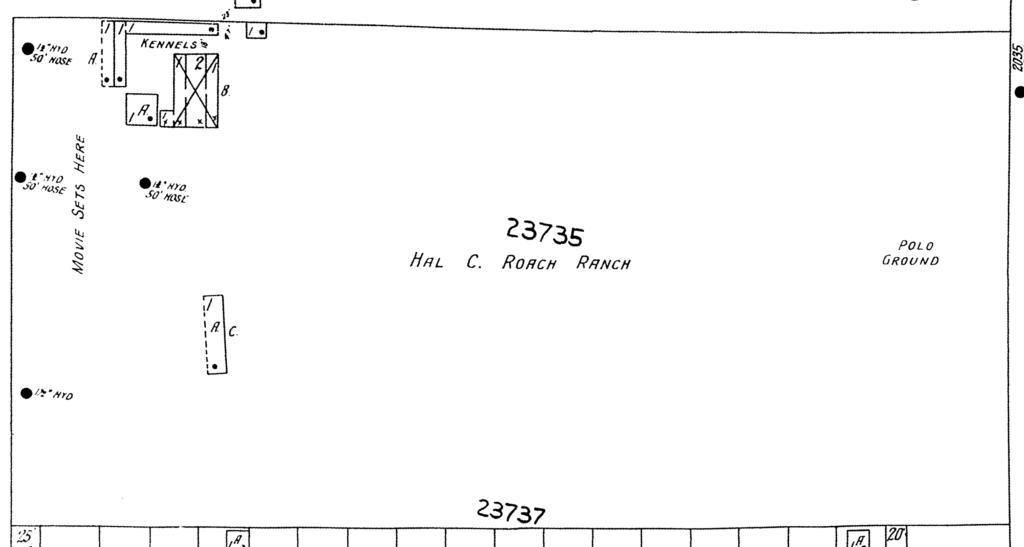

Less well known is the studio’s 10-acre backlot, called “Roach Ranch,” south of Don José de Arnaz’ ranch house. Hal Roach‘s studio had another outpost on the Arnaz land when Hal Roach Studios took over nearby Pacific Military Academy to house filmmakers during World War II – as part of “Fort Roach.”

Laurel & Hardy expert and author Richard W. Bann describes the Roach Ranch:

The Place was known as the Arnaz Ranch, or the Roach Ranch, or just “the ranch.” In the 1920s the terrain featured rolling hills and a flat area in the center. Roach and Will Rogers often played polo there during noon-hour workouts.

This rural, familiar looking locale served to brighten many outstanding comedies including The Hoose-Gow (1929) with Laurel & Hardy, Helping Grandma (1931) with Our Gang, and Fallen Arches (1933) with Charley Chase. There was a distinctive east west country lane, framed by a grove of beautiful eucalyptus trees. Long gone now, a dull housing tract stands there today, on a street called David Avenue. It slopes down looking east towards Robertson Boulevard, which can be seen carrying cars on the horizon in several shots during Towed in a Hole (1932). Hal Roach and Stan Laurel both drove south on Robertson Boulevard every day commuting between Beverly Hills and Hal Roach Studios in Culver City.

Mid-1920s – Rindge/Adamson/Marblehead Land Company, Westview Park & the Adohr Creamery

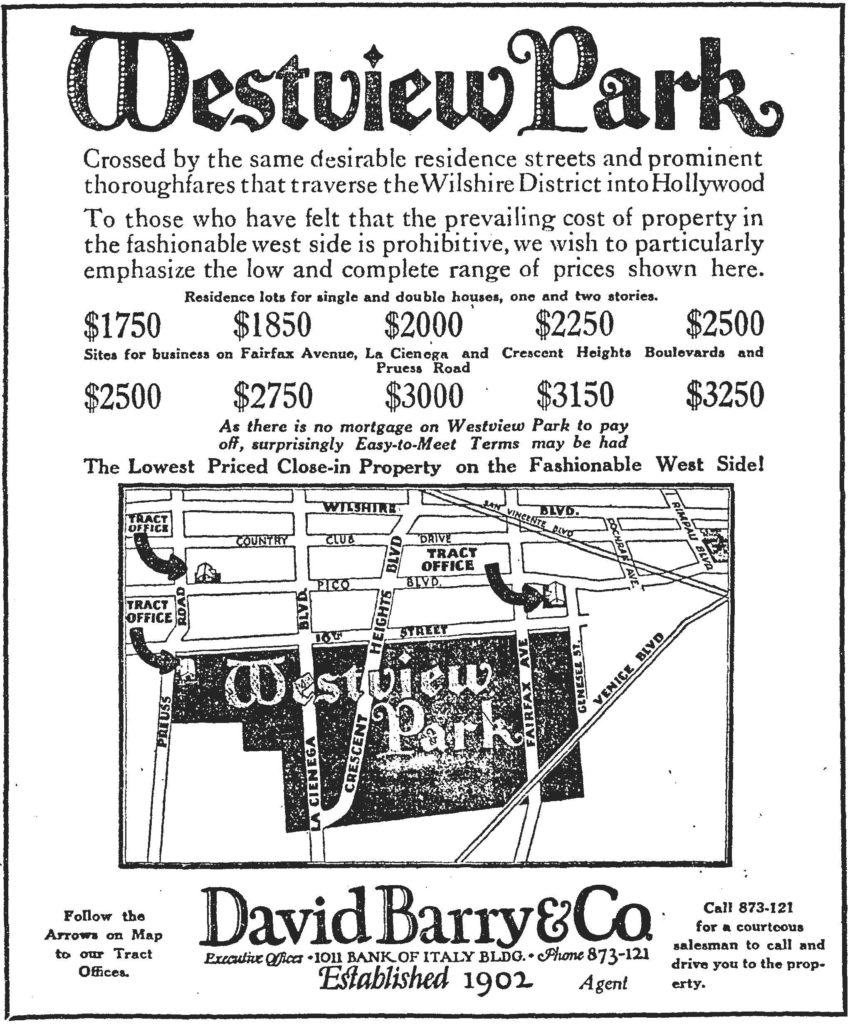

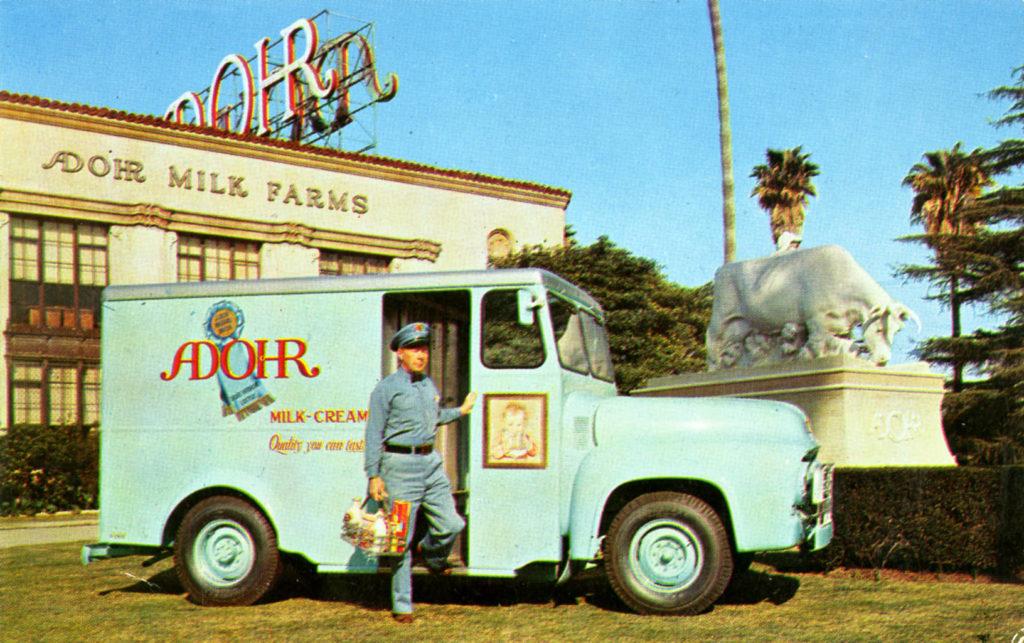

In the mid-1920s, the Rindge Family’s Marblehead Land Company developed the Westview Park neighborhood, Tract 8020 (a resubdivision of Arnaz’ Lots 2 and 3). Offering residential and business lots north and east of the $500,000 creamery, it was building on fourteen acres of its Arnaz Ranch land. “Centering around the new Adohr Creamery, now rapidly nearing completion, a community development calling for an expenditure of more than $3,000,000 is planned for the historic old Arnaz ranch” reported the L. A. Times on May 30, 1926.

On May 17, 1926, the L.A. Times reported that construction was under way for Adohr Creamery Company’s ambitious new plant

on a twelve-and-a-half-acre site at the corner of La Cienega Boulevard and Eighteenth Street.

With three shifts of men and a twenty-four-hour schedule the work of finishing the buildings and installation of machinery is going forward rapidly, and the owners expect the plant to be in operation early in June.

The “owners” of the creamery were the daughter and son-in-law of Frederick H. Rindge (1857–1905): Merritt H. Adamson (1888–1949) and Rhoda A. (Rindge) Adamson (1893–1962). “Between 1905 and 1940 with an estimated net worth of between US $700 million and US $1.4 billion, the Rindge family was widely considered one of the wealthiest in the world.” (Wikipedia.) The Adamsons also owned Adohr Milk Farm (a.k.a. Adohr Stock Farms) at 18000 Ventura Boulevard in Tarzana; in the 1920s, it had the “largest pure-bred herd of Guernsey cattle in the world.” (L. A. Times, Aug. 22, 1926.) The Rindge-Adamson family owned and operated the Adohr enterprises (named for Rhoda – her name spelled backward) from 1916 through 1966.

The Los Angeles Times provides this epitaph for the Creamery:

“By 1966, the price of cattle feed had skyrocketed and the Adamson trustees were forced to sell Adohr Farms to the Southland Corp., which would change hands again more than two decades later. Making room for the Ward Plaza shopping center and the Westview Park subdivision, the dairy was torn down in 1969.”

(L. A. Times, March 1, 1998.)

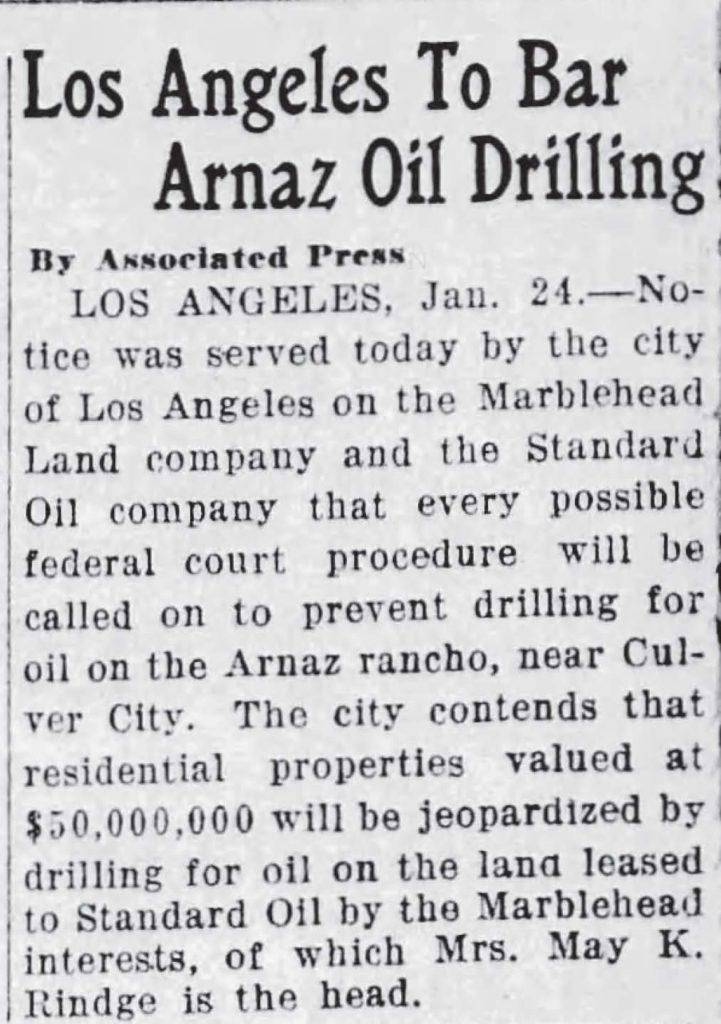

1910-1939 – Rindge Family Allows Oil Drilling, Leading to Conflict with Monte-Mar Vista Housing Developers

In March 1910, the Los Angeles Herald reported that a court would allow the Frederick Rindge estate to lease Lots 7 to 11 of the Arnaz tract to West Coast Oil for twenty years in exchange for “one-sixth of all the oil and gas produced.” It is unclear what came of that drilling effort. Without many neighbors, there did not appear to be much controversy or reporting. But the westward spread of housing development, and especially the fact that the houses were being sold to wealthy Angelenos, would put pressure on the Rindge family’s oil development in the next decade.

In 1927, at about the same time May Rindge’s daughter and son-in-law were building their creamery in the northeast section of the Arnaz Ranch, Rindge’s Marblehead Company leased the more westerly section to Standard Oil, which started drilling wells. That set off a decade-long battle with neighbors. Here is historian Nathan Masters’ telling:

A wildcat well next to a housing development was nothing special; oil companies were drilling across the Southland to find new petroleum deposits. Most communities were powerless to fight back, even as forests of derricks crowded their homes. But the well-heeled residents of Monte Mar Vista – today part of L.A.’s Cheviot Hills neighborhood – had the political muscle to elbow out oil operations.

The derrick stood inside an otherwise picturesque ravine. Cattle still grazed on the land, a 320-acre tract leased by Standard Oil, but the steel structure compromised Monte Mar Vista’s bucolic atmosphere and raised questions about noise and air pollution should the well strike black gold.

Before Standard Oil could turn its drill, Fred W. Forrester, a sales agent for Monte Mar Vista who also lived on one of the subdivision’s choice lots, filed suit. Joined by other real estate interests and two neighboring country clubs, Forrester obtained a temporary injunction against Standard Oil. As the litigation unfolded, the city rescinded a zoning variance it had issued to allow drilling on the site. Standard Oil and the landowner, May Rindge’s Marblehead Land Company, countered with a federal lawsuit that slowly worked its way up to the U.S. Supreme Court. But by 1931 the housing developers had won. The derrick came down, and the residents’ views were restored – until the ravine and hills became home to their own suburban housing tracts.”

Monte Mar Vista: Luxury Homes With a View (of an Oil Derrick)

In March 1928 Marblehead Land Company used the Arnaz Ranch as security for bonds it issued: “some 600 acres of land, partially subdivided, situate in Los Angeles, California, east of and adjoining Hillcrest Country Club. Appraised value 3,775,400.”

Before the decade’s end, drilling opponents would prevail, tolling the end for Marblehead’s Arnaz ranch.

1939 – Rindge Family Loses Arnaz Ranch Land due to Oil Drilling Ban, then Oil-Rich Dominguez Family Develops “Beverlywood” on it

When Marblehead Land Company sold 330 acres of Arnaz ranchland making way for the Beverlywood subdivision, it was a transaction between some of the biggest landowners of the past century, whose fortunes turned on oil. The buyers were scions of the Dominguez family – heirs to the Rancho San Pedro grant whose fortune was made in oil. The Rindge family, one-time owners of the Rancho Topanga Malibu Sequit and once among the wealthiest in the world, lost the right to drill for oil on the Arnaz tract, so they had to sell it amid the pressure of the Great Depression. In 1938, they had lost control of their Malibu ranch when their Marblehead Land Company was reorganized in bankruptcy. (L.A. Times, June 30, 1938.) Their Adohr Creamery remained until 1966.

The Dominquez family (among them Carsons, Del Amos, et al.) was unusual in that they had held on to most of their Rancho San Pedro land grant, rather than subdividing or losing it to litigation expenses or taxes. (Rancho San Pedro covered over 120 square miles: today’s Carson, Compton, Gardena, Hermosa Beach, Lomita, Manhattan Beach, Palos Verdes Estates, Rancho Palos Verdes, Redondo Beach, Rolling Hills, Rolling Hills Estates, Torrance, the western portions of Long Beach and Paramount, and the Los Angeles communities of Harbor City, Harbor Gateway, San Pedro, Terminal Island and Wilmington.) While rents may have kept them financially “comfortable,” they became extraordinarily wealthy after oil was discovered under their land. They sold their oil and rented land for tank farms and refineries, and they held it all through family corporations. Their oil wealth enabled them to buy the Rindge/Adamson family land – even if they could not extract the oil beneath it.

An inventory of the Rancho San Pedro Collection, held by California State University, Dominguez Hills, describes the Dominguez/Rindge transaction:

In 1939, H. H. Cotton and H. H. Jarrett headed a syndicate formed to purchase property known as the Arnaz Tract from the Marblehead Land Company, owned by Malibu heir and Los Angeles benefactress Rhoda Rindge Adamson. In April, 1939, the syndicate incorporated as the Beverly-Arnaz Land Company, with Cotton as President and Jarrett as Director. Also on the board was noted Los Angeles developer Walter H. Leimert. By 1940, the Arnaz Tract was being developed as Beverlywood, a subdivision located near Beverly Hills and what is now Century City in the Los Angeles area. The company was voluntarily dissolved in 1946 and its assets liquidated.

Both of the H. H.’s (Jarrett & Cotton) had connections to the Dominguez family and to the (future) Beverlywood area. Hardin Henry “H. H.” Jarrett (1888-1949) (husband to Dolores Maria Watson (1888–1924)) may have been familiar with the Arnaz ranch from his time working for the nearby Hauser Packing Company. And, before becoming a Beverlywood developer, Henry Hamilton “H. H.” Cotton (1880-1952) (husband to Victoria Lenora Carson (1879-1974)) lived up the hill in Monte-Mar Vista, which was initially promoted by his friend Ole Hanson. (An advertisement for Monte-Mar Vista listed several “prominent people” who had bought there, including Mr. Cotton.) Cotton and Hanson had partnered in developing San Clemente. (A Democratic political leader, Cotton’s 1926 San Clemente house, La Casa Pacifica, would later be Republican President Richard Nixon’s “Western White House.”)

The Romance of a Rancho article (from June 23, 1939) describes what forced the sale:

[D]uring the depression years, Mrs. Ringe’s [sic] empire began to collapse under its burden of taxes. Her holding company, the Marblehead Land Company, ran into serious financial difficulties. But the old Arnaz rancho Mrs. Ringe held onto stubbornly. Several years ago the company saw a prospect of developing the land as an oil field. Surrounding residents raised such a storm of protest, however, that the city council and planning commission of Los Angeles finally rejected the proposal by narrow margins. Recall of Mayor Shaw and ousting of his brother, Joe, put an end to oil-drilling schemes in the area.

[A] group of prominent Los Angeles financiers – whose names for various possible reasons [were] not being disclosed – formed the Beverly-Arnaz Land Company to purchase the tract for $750,000.

The Romance of a Rancho article predicted that an “ultra-modern home will probably occupy [the old ranch house’s] commanding site.” Ten years later, in 1949, this house at 1924 South Crest Drive was erected where Arnaz’ once stood.

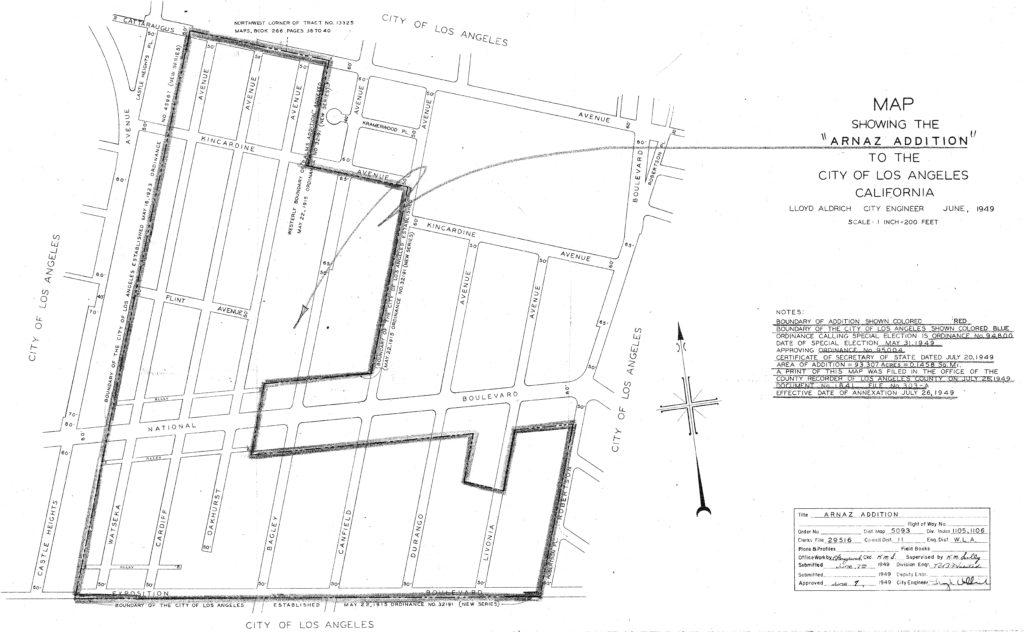

1949 – “Arnaz” Section Annexed

Until 1949, the “Arnaz” community remained an island of unincorporated Los Angeles County land. The “Arnaz” label had applied to the area since at least 1916, when Bullock’s Department Store listed “Arnaz” as a delivery area in a print advertisement. (L. A. Times, Dec. 10, 1916.)

On July 26, 1949, the City of Los Angeles annexed the Arnaz community’s “93 acres and 2400 citizens” after “the citizens of Arnaz voted 489 to 101 to become part of Los Angeles.” (L. A. Times, June 7, 1949.) Don José had bought his first interest in the land one hundred years before the Arnaz Addition to the City of Los Angeles.

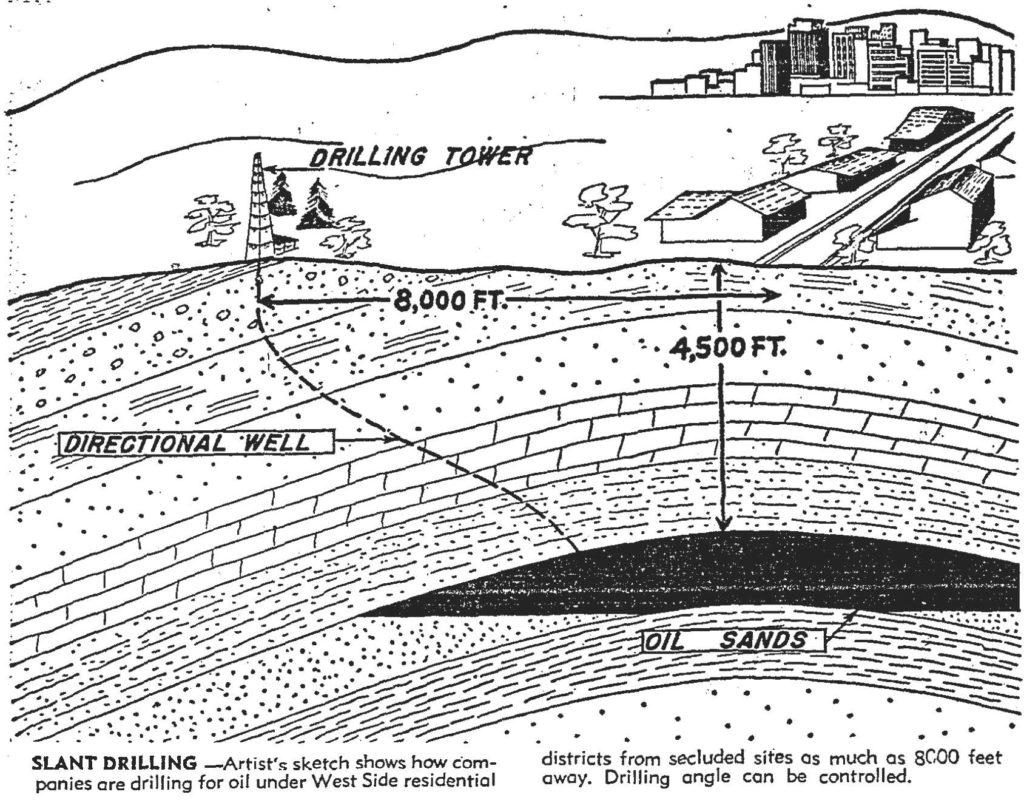

1950s – Oil Drilling Comes to Beverlywood – Despite Concern the Land will Revert to Rindge-founded Marblehead Land Company

Oil production ultimately returned to the Arnaz Ranch. With slant drilling starting in the 1950s, the pools of oil under Arnaz’ land would be extracted from wells on the Rancho Park Golf Course and Hillcrest Country Club. It was not without controversy tied to the Marblehead Land Company, which “[s]old to Beverly-Arnaz with the provision that if oil is produced, the property would revert back to Marblehead Land.” (L. A. Times, Sept. 14, 1958.)

Most residents supported drilling – and the royalties they would get. Measures to allay concerns included lowering the height of the derrick in Hillcrest Country Club ravine and shielding it with trees. (L. A. Times, Aug. 03, 1957.) By 1958, Signal Oil and Gas Company (founded by Samuel B. Mosher in 1922 on his Signal Hill extraction), had signed up the following percentages of property owners in these areas: east of Beverlywood, 82%; Rancho Park-Westwood Gardens, 85%; Palms Mar Vista, 81%; Cheviot Hills 57%; area north of Beverlywood, 70%.” (L. A. Times, Sept. 22, 1958.)

With 75% support, Signal was able to have the City create an oil drilling district. Beverlywood homeowners, who had been concerned about a fight with Marblehead, ultimately acceded. (See, L.A. Times, Jan. 31, 1960.)

The Last Remaining Signs

Today, Arnaz’ imprint on the land has been nearly erased. In Summer 1926, Arnaz Avenue, the main street east of Don José’s ranch house, was renamed. “Isadore B. Dockweiler and a number of property owners” wanted to simplify road names: Pruess, Arnaz, Seward, and Sherman became Robertson Boulevard in honor of developer George (G. D.) Robertson. (L.A. Times, Aug. 3, 1926.) The LA Street names website tells it best:

Arnaz Drive was born in 1922 with the clunky moniker Realtor Road. The word “realtor” had been coined in 1916 to distinguish real estate agents who belonged to the National Association of Real Estate Exchanges, but it made for an undesirable street name, so Realtor Road became Arnaz Drive in 1931. (Whoever renamed it must have missed the old Arnaz Avenue, which had become part of Robertson Boulevard in 1926.) The honoree was the late José de Arnaz (1820-1895), a Spanish merchant who had come to California in 1840. His land interests were most famously in Ventura, but he was active in Los Angeles as well: he set up shop here in 1844 and knew all the town fathers, from Abel Stearns to Eulogio de Celis. Arnaz eventually owned the 3,127-acre Rancho Rincón de los Bueyes (“Bulls’ Corner Ranch”), where Beverlywood and Cheviot Hills sit today – as did that long-lost Arnaz Avenue. His true legacy, however, may be his memoir, a highly detailed account of L.A.’s early days.