The Beverly Hills Citizen, June 23, 1939

(Volume XVII – No. 2, pages 9, 12)

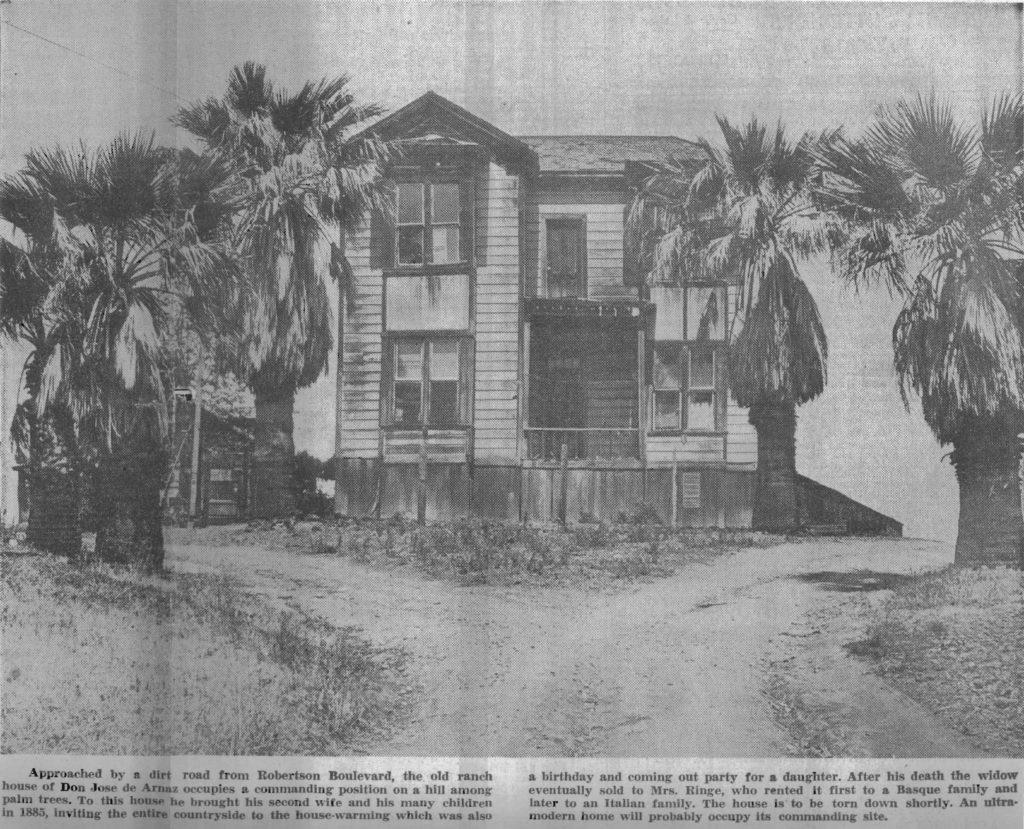

With the development during the next 90 days of the extensive acreage lying south of Pico and west of Robertson, another landmark – the old ranch house of Don Jose de Arnaz – will pass away, and with it the last vestige in this area of California pastoral life.

Gaunt among its palm trees on the hill, the decaying mansion has long aroused the curiosity of passersby. It seems to shrink back from the boulevard, its windows staring blankly to repel the inquisitive, its high front porch without steps for visitors, its front door barred all the way across by a balustrade.

While passersby are curious, persons living near the sagging brown structure say it has become a part of their lives. They have seen it dismal in the rain, sagging in the sun; they have observed its felicity against the sunset sky, its mysterious air at night. Day after day they have studied it through their windows, wondering about its origin, weaving stories about its history –but no one has been able to tell them.

This, then, is the story of the old house and of the ranch on which it stands, a story which not even the present occupants know.

Minorini Palace

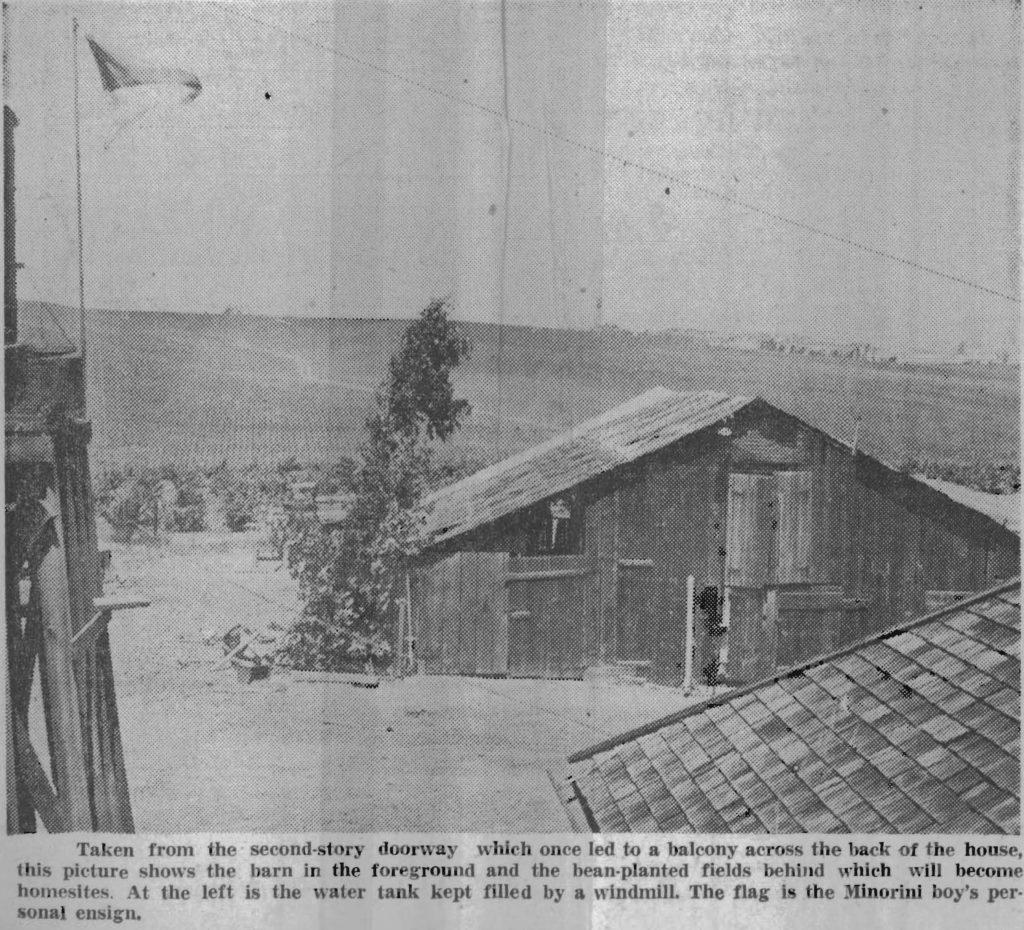

For the past 14 years the C. Minorini family has occupied the ‘‘palace,” as Mrs. Minorini terms it. When they moved in the bats and spiders moved out. They spent $700 making the lower floor habitable by covering the walls with plasterboard, putting in window glass, and installing plumbing, electric lights and gas.

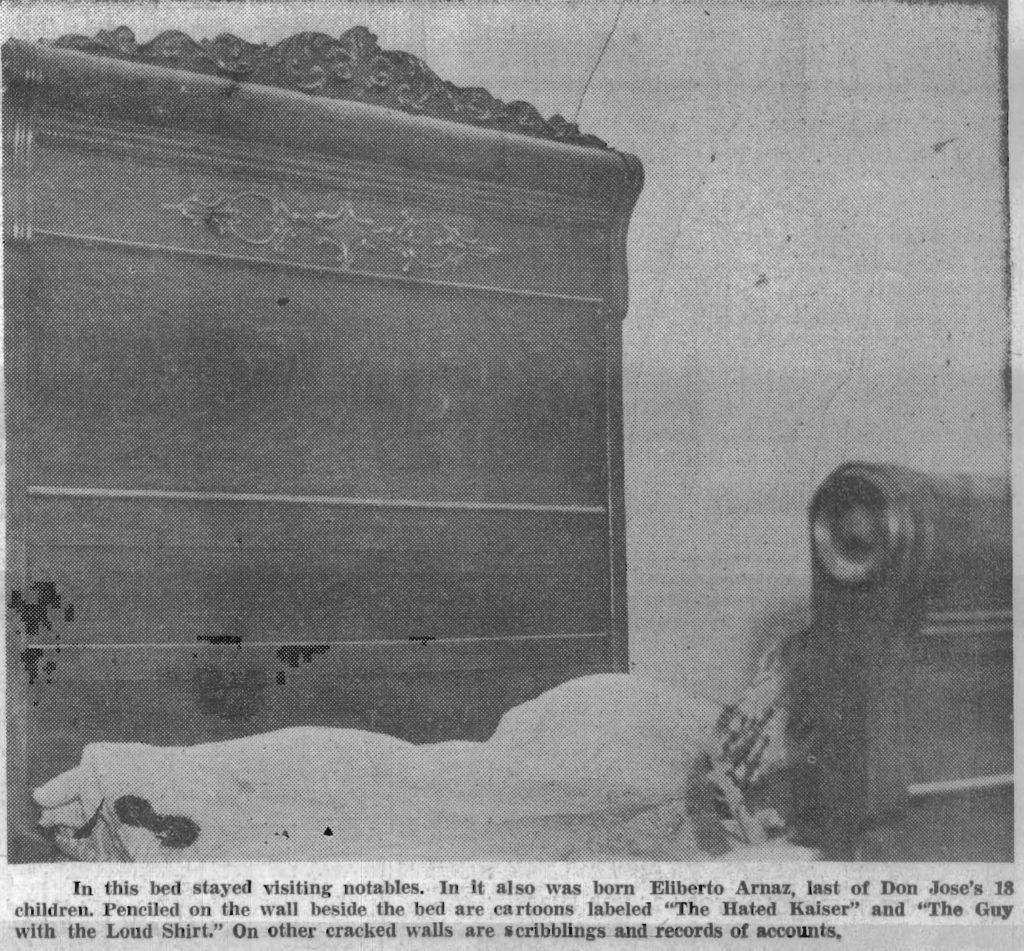

The six bedrooms on the second floor are empty except for a massive bedstead. Mrs. Minorini said Abraham Lincoln was supposed to have slept in the bed – but Lincoln was dead before the house was built. Certain it is, however, that many notables visiting Los Angeles stayed in the old house and used the bed.

A gold moulding, as bright as the day it was put into place, runs around the ceiling of the front bedroom. This room with its many-shuttered bay window was occupied by Senora Maria Camarillo y Arnaz herself. She used to say that from her window she could see every light in Los Angeles and could count them all.

Farms Ranch

Mr. Minorini has made his living farming the rolling 330-acre tract. Grapes occupy 20 acres, the vines being at least 70 years old, perhaps much older. Before prohibition the vineyard was larger by 25 acres. The rest of the tract is planted in lima beans.

The Minorinis have an expensive new car, a latest model radio, overstuffed furniture, and in the kitchen a green-tinted sink. When the land is sub-divided they expect to move somewhere else in the neighborhood, so that their daughter can finish at Alexander Hamilton High School and their son at Holy Spirit School.

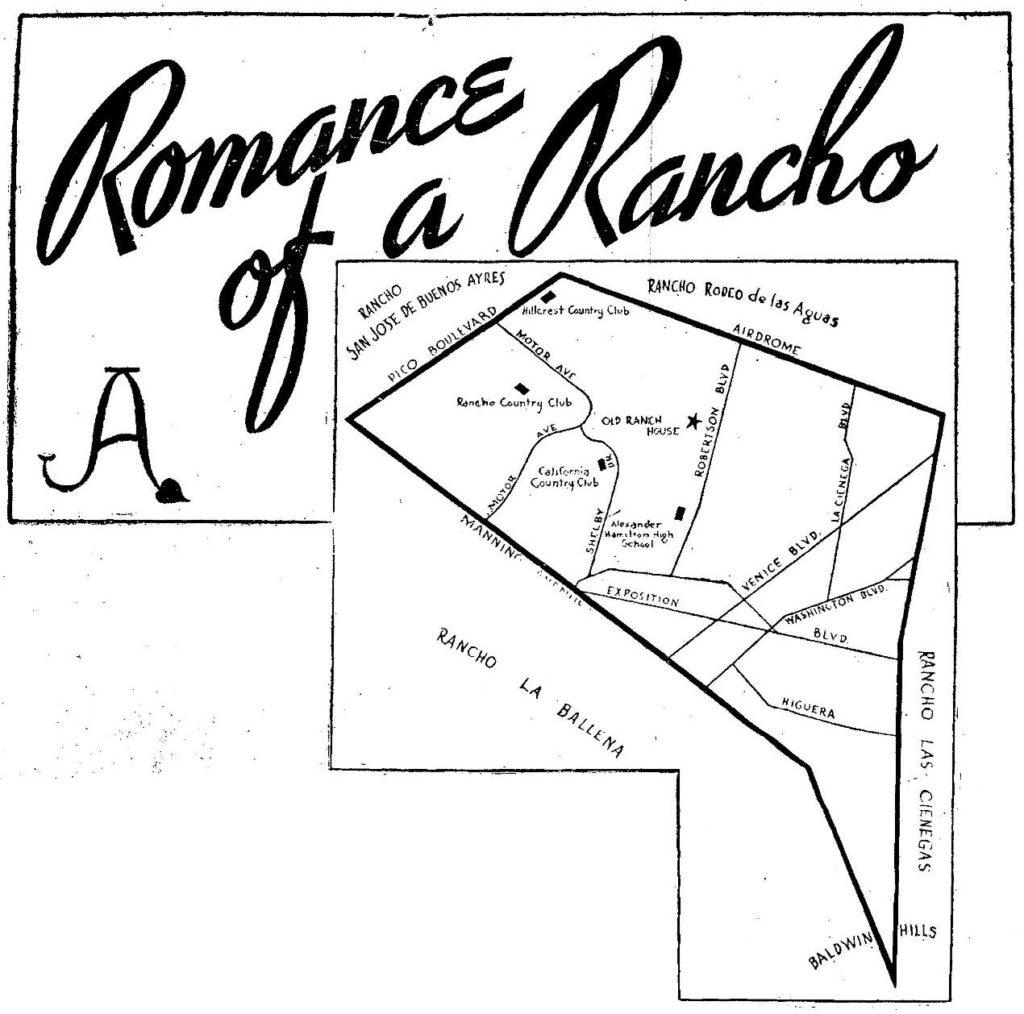

Boundaries of the original 3100-acre rancho included land on which the homes of Monte Mar Vista and Cheviot Hills now stand, as well as the Rancho, Hillcrest and California country clubs, the Pacific Military academy, the studios of Hal Roach and Selznick International, and part of the Baldwin Hills.

Petition

While extensive by modern standards, the rancho was not considered large in Spanish days. Situated off the main highway of travel, it was not settled until 1821, the last year of Spanish rule, when Los Angeles had 770 residents. On December 5th of that year the military commander of Los Angeles, Jose de la Guerra y Noriega, received the following petition:

To the Senor Captain:

“Bernardo Higuera and Cornelio Lopez, citizens of the Pueblo de Nuestra Senora la Reina de Los Angeles, and under the command of your honor, with the greatest respect and submission before your Excellency, appear and say that, possessing at the time a number of cattle and not having any place so as properly to he able to keep than with grazing land of sufficient extent, therefore ask and beseech your extreme clemency to be pleased to grant to them the tract within this vicinity called Corral Viejo del Rincon, so that they may be able to place a corral for herding the said cattle unless it does some injury to the neighboring residents – a favor they expect from your extreme goodness and for which they will recognize themselves very grateful. May God preserve you many years.”

Two days later, on the margin of the petition, Captain Noriega wrote:

“Pueblo de Nuestra Senora de Los Angeles. Dec. 7, 1821. It is granted if no prejudice result to the community. Noriega.”

The “Corner”

From that day onward, the ranch became known as Rincon de los Bueyes – “Corner of the Cattle.” The “corner” was a ravine at the southernmost tip of the rancho which served as a natural corral. The “57” sign today is just east of that ravine.

Lopez soon quarreled with Higuera, leaving the latter in possession. Higuera built two houses 1822, living on the ranch with his family for 12 years. In 1834 he moved to Los Angeles with wife, Maria Rosalia Polomares, leaving his brother Policarpio in charge.

In 1848, asserting that his brother had abandoned the ranch, Policarpio formally claimed the rancho for himself, for another brother Mariano, for Higuera’s son Francisco, and for Pedro Mendez. When Policarpio died, Mendez sold his share of the rancho to Policarpio’s widow for four tame cows valued at six dollars each. From then on, while the ownership was divided among the family, the masters of the rancho were Francisco and Secundino, sons of the official grantee.

Trophy of War

Francisco fought against the Americans in the engagement of San Pasqual, wounding Captain Gillespie, commander of the Los Angeles garrison. He appropriated the captain’s fine saddle. Afterward, Francisco continued living on the rancho, raising a family of nine children in an adobe house on the bank of Ballona creek. Near his house he had an orchard of apple, pear, pomegranate and olive trees.

In another adobe house on high ground at the west end of the rancho lived his brother, Secundino. This brother in 1849 sold his portion to Don Jose de Arnaz, who also, in 1867, bought most of Francisco’s portion except the triangular part south of what is now Washington boulevard. In later years, Higuera’s saloon on the site of the present Cotton Club was the gathering place for cowboys from miles around.

The sales, however, could not be considered as final until the Higueras had proved their claims before the United States Land Commission. From 1852 until 1869 they, aided by the influential Arnaz, fought to hold the rancho. The litigation was complicated by the fact that squatters had moved in on parts of the land. Descendents of these squatters became social and business leaders of Los Angeles. Arnaz always carried a rifle, and used it in more than one instance, finally evicting most of the squatters from the land and clearing the title. The patent was eventually issued August 27, 1872.

Widely Known

In Don Jose de Arnaz the rancho had an owner known throughout the state, who as a young man had sold Mexican saddles to the rancheros and Chinese shawls to their wives, and who in the prime of life owned the 48,882 acres of Ventura Mission and before he died had given his name to 18 children.

Arnaz was born in the town of Camillas, province of Santander, Spain, on March 22, 1820. At the age of 16 he shipped as a cabin boy to Havana, where he stayed for three years, working as a clerk by day and studying medicine at night. He abandoned his studies to go to Mexico to collect an inheritance but was cheated out of everything. His funds exhausted, he entered the employ of a German merchant, Enrique Virmond, and within a year was supercargo on Virmond’s bark Clarita engaged in trade with California.

Job of the supercargo was to dispose of fancy serapes, gold-embroidered suits with silver buttons, hats, boots, saddles, shawls, sugar and brandy in exchange for hides and tallow. Arnaz visited all the important families of California, always being a welcome visitor as the bearer of news and the source of luxuries. To attract San Diegans aboard ship to see the large display of merchandise, he one time staged a ball which lasted eight days. Families came from far in the interior to enjoy themselves and buy Arnaz’s goods. A cargo valued in Alcapulco, Mexico, at $10,000 would be traded over a period of months for California hides and tallow worth $60,000 or more.

Opens Store

As supercargo on the Clarita and later on the frigate Joven Guipuzcoana he soon made enough money to open a store of his own in Los Angeles. This store was several times pillaged by the cholos, lawless soldiers which General Micheltorena had recruited from the jails of Mexico. As a former medical student he gave his customers advice on minor ailments and had a shelf of drugs.

With the profits from his store, Don Jose branched out into ranching. Five years after being penniless in Mexico he was able to lease the extensive lands of ex-Mission San Buenaventura and a year later to buy them for $1630 through his friend, Governor Pio Pico.

Shortly after Arnaz acquired the mission the American occupation occurred. Several years previous, Arnaz having been aboard Ship in San Francisco harbor, was taken prisoner by Commodore Jones in the later’s premature “capture” of San Francisco, which then consisted of six buildings. At the mission ranch, early in 1847, he was again taken prisoner, this time by Colonel Fremont, but won his release by furnishing Fremont with horses, saddles and beef for Fremont’s march into Los Angeles.

Founds Ventura

Following the war Arnaz founded the town of Ventura by offering free land to settlers. In 1850 he sold what remained of his 48,882 acres to [Dr. Manuel Antonio Rodriguez de Poli]. He continued as Ventura’s first citizen, however, being the judge and the supervisor of schools. His large adobe house is still standing in Ventura. To this house he took his bride, Maria Mercedes de Avilla, who bore him 10 children during the 10 years of their married life. In this house, following her death, he left his children when two years later, 1869, at the age of 49, he married Maria Camarillo and took her to live in San Jose where he became the first druggist. The town of Camarillo was named for her family. Her brother Juan, who died only two years ago, left five nieces and nephews ranches of about 260 acres each and had enough left over to bequeath extensive acreage for St. John’s Major Seminary named in his honor.

From San Jose, with his growing family, Arnaz moved back to Los Angeles, and when litigation in connection with Rancho Rincon de los Bueyes was finally settled, he constructed the 15-room house which became a showplace. To the housewarming, which also marked the sixteenth birthday of his daughter, Prexcedes, now residing on South Oxford street, he invited everybody from what is now Western avenue to the sea. Over 200 guests sipped his wines and danced throughout the night.

Wines Famous

Wines produced on the rancho became famous throughout the valley. His daughter recalls that three immense wooden vats stood in back of the house in which the grapes were stamped by men in hip-boots. The wine was then made in the large cellar, eight dozen beaten eggs going into every 50-gallon tank to produce a clear sparkling vintage. At all hours of the day and night, ranchers from miles around knocked at the kitchen door to buy jugs of wine from Arnaz’s majordomo.

Arnaz also raised cattle, pasturing them in the area bounded by Pico, Washington, Robertson and La Cienega boulevards. Three times a year he sent steers to the slaughterhouse at the intersection of Washington and Adams Boulevard.

Divides Ranch

Before his death at the age of 74, on February 1, 1895, Don Jose had drawn a will dividing his rancho into two parts. He drew a line bisecting the rancho approximately north and south, along the eastern boundaries of what today is the Hillcrest Country Club. All west of this line went directly to surviving children by his first wife; all lying east of the line went to his widow to be held in trust for herself and her surviving children.

Children by his first wife were Elvira Arnaz and Ventura Arnaz Wagner, both living in Ventura; McIvio Arnaz, of Salinas; Amanda Arnaz Sepulveda, of Los Angeles; Virginia de Anguisola, Adella, Camilla, Mercedes, Jose Maria, and Luis, all deceased. They received shares varying from 80 acres to 200 acres, depending upon the value of the land, whether it was level or hilly, watered or dry. These shares, totaling over 1000 acres, they disposed of at different times to different parties.

Enter Mrs. Ringe

The other half of the rancho was kept intact by the widow, for 10 years. She continued raising cattle, making wine, and growing grain, aided by a trusted foreman named Olvera. In 1904, with court approval, she sold the property to Mrs. Ringe for $125,000, of which the court awarded her $40,000, the remaining $85,000 being divided among her children in proportion to the value of the tracts Don Jose had set aside for them.

However, 81 acres intended for Eliberto Arnaz, the youngest, was not included in the transaction – because he was still a minor and the property had to be held until he came of age. Land values began soaring about that time, and in 1911 Eliberto, having attained his majority, was offered $700 an acre or $56,700 for his share, which lay between Robertson and La Cienega boulevards. He sold – to his regret in 1918 when the same property was selling for $6000 an acre. At that rate his 81 acres would have been worth $486,000.

Fights Progress

For 35 years Mrs. Ringe held the land she purchased, successfully fighting every effort to extend Beverly, Reeves, Rexford, Glenville, Doheny, Oakhurst and other streets through the property to Culver City. On part of the property the Ringe interests built the Adohr plant (Adohr is Mrs. Ringe’s first name spelled backwards). The remainder lay unimproved while surrounding areas developed into fine residential areas.

Then, during the depression years, Mrs. Ringe’s empire began to collapse under its burden of taxes. Her holding company, the Marblehead Land Company, ran into serious financial difficulties. But the old Arnaz rancho Mrs. Ringe held onto stubbornly. Several years ago the company saw a prospect of developing the land as an oil field. Surrounding residents raised such a storm of protest, however, that the city council and planning commission of Los Angeles finally rejected the proposal by narrow margins. Recall of Mayor Shaw and ousting of his brother, Joe, put an end to oil-drilling schemes in the area.

As hopes vanished for replenishing the seriously depleted Ringe coffers with money derived from oil, and as back taxes mounted staggeringly, the Marblehead Land Company was reorganized.

Consents To Sale

Long coveted by realty developers, the 330 remaining acres of the old rancho constituted the last important unsubdivided area in western Los Angeles. Five years ago Mrs. Ringe would have rejected $10,000 an acre or $3,300,000 for the tract. She valued it highly and reported it at nearly that figure for tax purposes. But at last, under the reorganization plan, Mrs. Ringe had to consent to disposal of the property.

Taking advantage of this opportunity and working closely with the Marblehead company, a group of prominent Los Angeles financiers-whose names for various possible reasons are not being disclosed-formed the Beverly-Arnaz Land Company to purchase the tract for $750,000. Head of the new company is H. H. Jarrett, who has charge of realty operations for various holding companies.

Deal A Loss

Because both actual and tax valuation of the property was much higher than the sale price, the Marblehead company, headed by Howard C. Bonsall, shows a loss on the deal and thus escape taxes which on other tracts valued at $750,000 might amount to nearly $400,000.

The Beverly-Arnaz Land Company put the Walter H. Leimert Company in charge of development of the property. Leimert engaged George Gibbs, Eastern landscape architect, to lay the tract. Gibbs made nearly 30 studies of the land: finally drafting a plan which is expected to be final. It calls for extensive tree-planting, impressive entrance gates at several points, and a landscaped strip 15 to 25 feet wide along the entire frontage on Robertson Boulevard. No lots will face on Robertson. Streets will follow natural contours to avoid scarifying the hills. Restrictions will provide for moderately priced homes.

For valuable assistance in preparing this first comprehensive study of the Rancho Rincon de los Bueyes, thanks are due to Prexcedes Arnaz de Lavigne, whose memory and whose research into old archives provided many facts; to W. W. Robinson, of the Title Guarantee and Trust Company, whose booklet “Culver City” was of much help; to Nellie Van de Grift Sanchez, whose translation of a document by Don Jose de Arnaz appeared in “Touring Topics” in 1928, and to other sources.

Please note the alternate spelling of Rindge/Ringe in the article. ed.